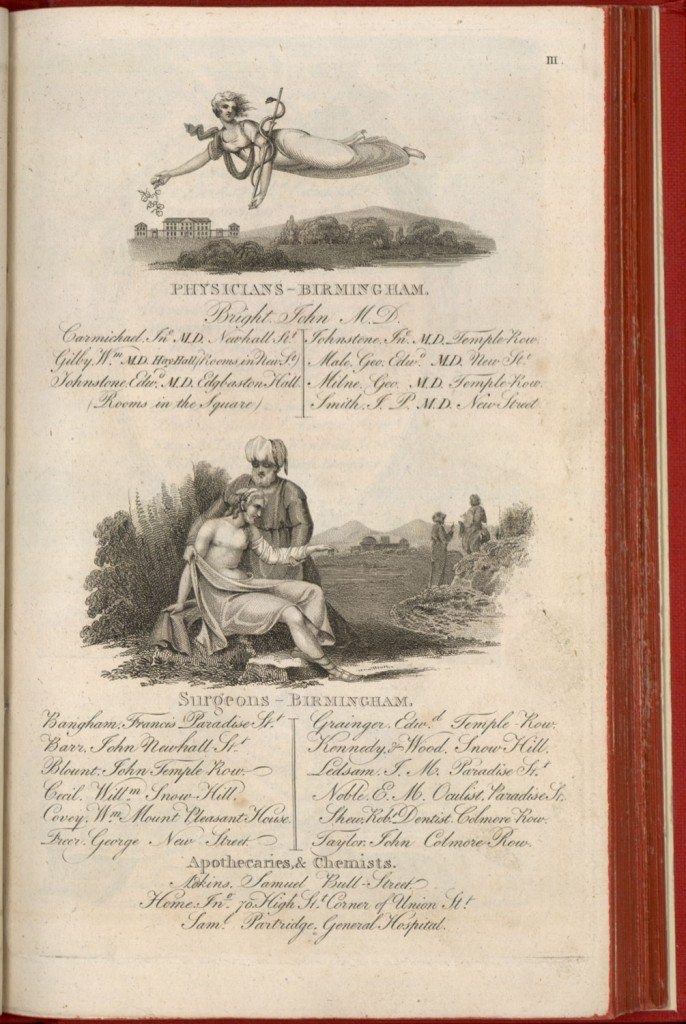

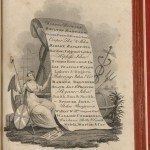

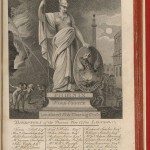

Physicians, Surgeons, Apothecaries and Chemists in Birmingham

The top part of the plate represents Hygeia, the Greek Goddess of Health, strewing her medicinal virtues over the earth. The Romans used the name Salus for the goddess. Birmingham General Hospital stands in the background. Eight physicians, all M Ds, are listed and seven have addresses. Five are located in New Street or Temple Row, but one Edward Johnstone resides at Edgbaston Hall, the former residence of Dr William Withering, one of the Lunar Men.

The lower compartment depicts an emblematic device of the Good Samaritan who aided an injured traveller at the roadside. The story would be familiar to readers of the Directory from the life of Jesus in the New Testament. Twelve Surgeons are named with their addresses, one of whom is described as a dentist and another as an oculist who would perform operations on the eye. The names and locations of three apothecaries and chemists follow the list of surgeons.

The advertisement accurately presents the medical class structure by the early 19th century. Physicians were the aristocracy of medical practitioners; university graduates who could command high salaries. Their training in what we now call science gave them an insight into the body and disease, but there were huge variations in the standards of medical education and no regional regulation of medical licensing. Surgeons were not usually graduates, but were apprenticed and learned their craft of surgery whilst working. Traditionally a low status occupation, they were shaking away their origins as barber surgeons who cut hair as well as performed operations. The advent of anatomy classes, textbooks on surgery and general infirmaries in the late 18th century “contributed to surgery’s emergence from a manual craft into a scientific discipline involving physiological investigation” (Porter, 1997, p 280-281). Apothecaries who dispensed drugs were licensed in London, but “unregulated chemists and druggists blossomed, together with quacks and unorthodox practitioners” (Porter, 1997, p 288).

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

A Catalogue of Commerce and Art: Bisset’s Magnificent Guide for Birmingham, 1808

A Catalogue of Commerce and Art: Bisset’s Magnificent Guide for Birmingham, 1808

Frontispiece to Bisset’s Magnificent Directory

Frontispiece to Bisset’s Magnificent Directory

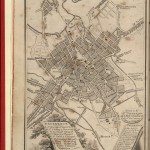

Plan of Birmingham, drawn by J. Sherrif of Oldswinford, late of the Crescent Birmingham

Plan of Birmingham, drawn by J. Sherrif of Oldswinford, late of the Crescent Birmingham

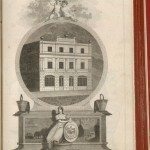

Birmingham Fire Office

Birmingham Fire Office

Bankers and Public Companies in Birmingham

Bankers and Public Companies in Birmingham

Physicians, Surgeons, Apothecaries and Chemists in Birmingham

Physicians, Surgeons, Apothecaries and Chemists in Birmingham

Attorneys at Law in Birmingham

Attorneys at Law in Birmingham

Sword, Gun and Pistol Manufacturers in Birmingham

Sword, Gun and Pistol Manufacturers in Birmingham

Mercers, Linen Drapers, Haberdashers, Hosiers and Lacemen in Birmingham

Mercers, Linen Drapers, Haberdashers, Hosiers and Lacemen in Birmingham

J Taylor, Gold and Silversmith, Jeweller, Tortoiseshell and Ivory Box and Toy Manufacturer, Birmingham

J Taylor, Gold and Silversmith, Jeweller, Tortoiseshell and Ivory Box and Toy Manufacturer, Birmingham

Cabinet Makers, Upholsterers, Gun Makers and Saddlers in Birmingham

Cabinet Makers, Upholsterers, Gun Makers and Saddlers in Birmingham

Birmingham in Miniature or Richard’s Magazine for the Manufacturers of Birmingham and its Vicinity

Birmingham in Miniature or Richard’s Magazine for the Manufacturers of Birmingham and its Vicinity

Bankers in Birmingham and Businessmen adjacent to Birmingham

Bankers in Birmingham and Businessmen adjacent to Birmingham

Merchants in Birmingham

Merchants in Birmingham

Miscellaneous Businesses in New Street, Birmingham

Miscellaneous Businesses in New Street, Birmingham

Miscellaneous Businesses in High Street, Birmingham

Miscellaneous Businesses in High Street, Birmingham

Gun Makers in Birmingham

Gun Makers in Birmingham

Inns, Hotels and Taverns and Swinney’s Type Foundry in Birmingham

Inns, Hotels and Taverns and Swinney’s Type Foundry in Birmingham

Factors or Commercial Agents in Birmingham with a view of the Crescent and Wharf

Factors or Commercial Agents in Birmingham with a view of the Crescent and Wharf

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Birmingham with a View of St Philip’s Church

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Birmingham with a View of St Philip’s Church

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Birmingham with Emblems of their Trade

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Birmingham with Emblems of their Trade

Henry Clay, Japanner, and Artists in Birmingham

Henry Clay, Japanner, and Artists in Birmingham

Sword Makers in Birmingham

Sword Makers in Birmingham

Brass Founders with a view of the Brass House in Broad Street, Birmingham and Miscellaneous Businesses

Brass Founders with a view of the Brass House in Broad Street, Birmingham and Miscellaneous Businesses

Toy Makers in Birmingham with a View of the Navigation Offices

Toy Makers in Birmingham with a View of the Navigation Offices

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Birmingham with a View of St Paul’s Chapel

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Birmingham with a View of St Paul’s Chapel

Japanners in Birmingham and a View of the Park Glass House

Japanners in Birmingham and a View of the Park Glass House

Cards of different Professions and Businesses in Birmingham

Cards of different Professions and Businesses in Birmingham

Miscellaneous Businesses in Birmingham with a View of the Town from the Warwick Canal

Miscellaneous Businesses in Birmingham with a View of the Town from the Warwick Canal

Button Makers in Birmingham

Button Makers in Birmingham

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Deritend near Birmingham

Miscellaneous Professions and Businesses in Deritend near Birmingham

View of Matthew Boulton’s Soho Manufactory and Royal Mint Offices in Handsworth near Birmingham

View of Matthew Boulton’s Soho Manufactory and Royal Mint Offices in Handsworth near Birmingham

View of the Eagle Iron Foundry and Mr. Whitmore’s Engineering Works in Birmingham

View of the Eagle Iron Foundry and Mr. Whitmore’s Engineering Works in Birmingham

View of Lloyd’s, New Hotel and Hen and Chickens Inn, New Street, Birmingham

View of Lloyd’s, New Hotel and Hen and Chickens Inn, New Street, Birmingham

Exterior and Interior View of Jones, Smart and Company’s Glass Manufacturers, Aston Hill, Birmingham

Exterior and Interior View of Jones, Smart and Company’s Glass Manufacturers, Aston Hill, Birmingham

Thomason’s Button and Toy Manufactory, Church Street, Birmingham

Thomason’s Button and Toy Manufactory, Church Street, Birmingham

View of the Westminster Life and British Fire Insurance Offices, Strand, London, with a List of the Directors. J. Gottwaltz, Birmingham Agent

View of the Westminster Life and British Fire Insurance Offices, Strand, London, with a List of the Directors. J. Gottwaltz, Birmingham Agent

The Phoenix Fire Office, Lombard Street and Charing Cross, London, with a List of the Directors. J. Farror, Birmingham Agent.

The Phoenix Fire Office, Lombard Street and Charing Cross, London, with a List of the Directors. J. Farror, Birmingham Agent.

Two Manufacturers, a School, an Engineer and an Inn near Birmingham

Two Manufacturers, a School, an Engineer and an Inn near Birmingham

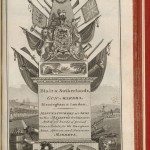

Blair and Sutherlands, Gun Makers, Brook Street and Harper’s Hill, Birmingham

Blair and Sutherlands, Gun Makers, Brook Street and Harper’s Hill, Birmingham

Button Makers and other Businesses of Birmingham

Button Makers and other Businesses of Birmingham

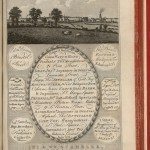

View of Birmingham from Aston Wharf with the Names of various Businesses

View of Birmingham from Aston Wharf with the Names of various Businesses

Miscellaneous Metal Manufacturers and other Businesses in Birmingham

Miscellaneous Metal Manufacturers and other Businesses in Birmingham

Toy Maker and Japanners in Birmingham

Toy Maker and Japanners in Birmingham

Surveyor, Sutton Coldfield and Coach Spring Manufacturers, Birmingham

Surveyor, Sutton Coldfield and Coach Spring Manufacturers, Birmingham

A Bookseller and list of Appraisers and Auctioneers in Birmingham

A Bookseller and list of Appraisers and Auctioneers in Birmingham

Merchants and Factors in Birmingham

Merchants and Factors in Birmingham

Hepinstall and Parker’s File Manufactory, Ann Street, Birmingham and Walsall, Staffordshire

Hepinstall and Parker’s File Manufactory, Ann Street, Birmingham and Walsall, Staffordshire

Miscellaneous Traders, Professions and Manufacturers in Birmingham

Miscellaneous Traders, Professions and Manufacturers in Birmingham

Trade Cards for various Businesses in Birmingham

Trade Cards for various Businesses in Birmingham

View of Warstone Brewery, Warstone Lane, Birmingham, belonging to Alex Forrest and Sons

View of Warstone Brewery, Warstone Lane, Birmingham, belonging to Alex Forrest and Sons

Various Toy Makers and Jewellers in Birmingham

Various Toy Makers and Jewellers in Birmingham

Thomas Robinson, Chemist, and Roberts, Jeffery and Co, Button and Toy Manufacturers, Snow Hill, Birmingham

Thomas Robinson, Chemist, and Roberts, Jeffery and Co, Button and Toy Manufacturers, Snow Hill, Birmingham