A Letter from a Mechanick in the busy Town of Birmingham, to Mr. Stayner, a Carver, Statuary, and Architect, in the sleepy Corporation of Warwick

Image: South-West Prospect of Birmingham, 1829, attributed to Frederick Calvert. Watercolour on Paper.

Image from: Birmingham Museums & Art Gallery

If you can leave your Borough, still and fair,

To breathe awhile in more sulphureous Air; / ……

When broad awake, for Vulcan’s Province steer

Each Cyclop will rejoice, to see famed Stayner here, / ……

You’ll see the cloud above, the thund’ring Town below, / ……

You’ll be convinc’d that Vulcan’s Forge is here; / ……2

According to Langford, this poem was first printed in the Birmingham Gazette in February 1751, although it was purported to have been written in 1733. In the title, the contrast between ‘busy’ Birmingham and ‘the sleepy Corporation of Warwick’ is telling. One traditional, although arguable, reason given for Birmingham’s industrial growth and success is that it was not (until the nineteenth century) an incorporated town and was, therefore, free from many restrictions on residents and work-practices, and so could develop more freely. The writer of this poetic ‘Letter’ is gently boasting when contrasting Birmingham’s greater commercial success with incorporated Warwick.

As in The Cyclops there is the metaphor of the Cyclops for the metalworker and, again, Vulcan reigns. Among items listed in the poem are ‘toys’. These were not playthings to amuse children. In the eighteenth century ‘toys’ was a collective term for a wide variety of small, frequently metal, objects such as buttons, shoe buckles, boxes, inkstands and ‘sugar knippers’. Birmingham produced many of these, especially buttons and buckles, in large quantities.

Two-thirds into the poem the scene changes and moves a few miles north-west:

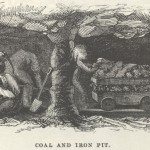

Beneath Old Wedgb-ry’s burning Banks …

… Thousands …, with glaring Eyes,

In Subterraneous Caverns … / … sap like Moles,

Supplying every Smithy Hearth with Coals;

There let them delve, whilst in the growing Town

In jolly Bacchanals our Cares we drown. ………

A footnote to the poem explains that ‘Old Wedgb-ry’ (i.e. Wednesbury) was ‘famous for Coal Mines, and subterraneous Fires’. This hints at one of the very real dangers of sapping like a mole for coal to get one’s daily bread. And whilst there were smithies in the Black Country, much Wednesbury coal fuelled Birmingham’s industry. There was a symbiotic relationship between the suppliers and users of the coal, with, on each side, the owners being the main gainers. The thousands of workers benefited more or less. However, the poet points concisely to a contrast between the effects on urban and rural landscapes and social conditions caused by great exploitation of a natural resource. ‘Whilst in the growing Town’ the fires in the forges of Birmingham were usually under control, in the coalfields were ‘burning Banks’, where the land itself was being consumed.

2 Anonymous, A Letter from a Mechanick in the busy Town of Birmingham, to Mr. Stayner, a Carver,

Statuary, and Architect, in the sleepy Corporation of Warwick. Pages 41-42, Vol. 1, John Alfred Langford (Compiled and Edited by), A Century of Birmingham Life, 2 vols, second edition, W.G.Moore & Co., Birmingham, 1870.

Continue browsing this section

Poetry and the Industrial Revolution in the West Midlands c. 1730-1800

Poetry and the Industrial Revolution in the West Midlands c. 1730-1800

The Cyclops: Addressed to the Birmingham Artisans, Anonymous

The Cyclops: Addressed to the Birmingham Artisans, Anonymous

A Letter from a Mechanick in the busy Town of Birmingham, to Mr. Stayner, a Carver, Statuary, and Architect, in the sleepy Corporation of Warwick

A Letter from a Mechanick in the busy Town of Birmingham, to Mr. Stayner, a Carver, Statuary, and Architect, in the sleepy Corporation of Warwick

Answer to Dardanus’s

Answer to Dardanus’s

Industry and Genius; or, the Origin of Birmingham. A Fable

Industry and Genius; or, the Origin of Birmingham. A Fable

Labour and Genius: or, the Mill-stream, and the Cascade. A Fable

Labour and Genius: or, the Mill-stream, and the Cascade. A Fable

Inland Navigation, An Ode. Humbly Inscribed to The Inhabitants of Birmingham, And Proprietors of the Canal

Inland Navigation, An Ode. Humbly Inscribed to The Inhabitants of Birmingham, And Proprietors of the Canal

Edge-Hill: a Poem, in four Books

Edge-Hill: a Poem, in four Books

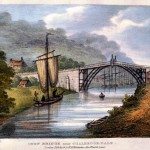

Colebrook Dale

Colebrook Dale

The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus

The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus

The Botanic Garden, Erasmus Darwin

The Botanic Garden, Erasmus Darwin

Ramble of the Gods through Birmingham. A Tale, James Bisset

Ramble of the Gods through Birmingham. A Tale, James Bisset

Rural Happiness. To a Friend and Moonlight: in the Country

Rural Happiness. To a Friend and Moonlight: in the Country