Working Practices and Conditions in the Birmingham Brass Industry

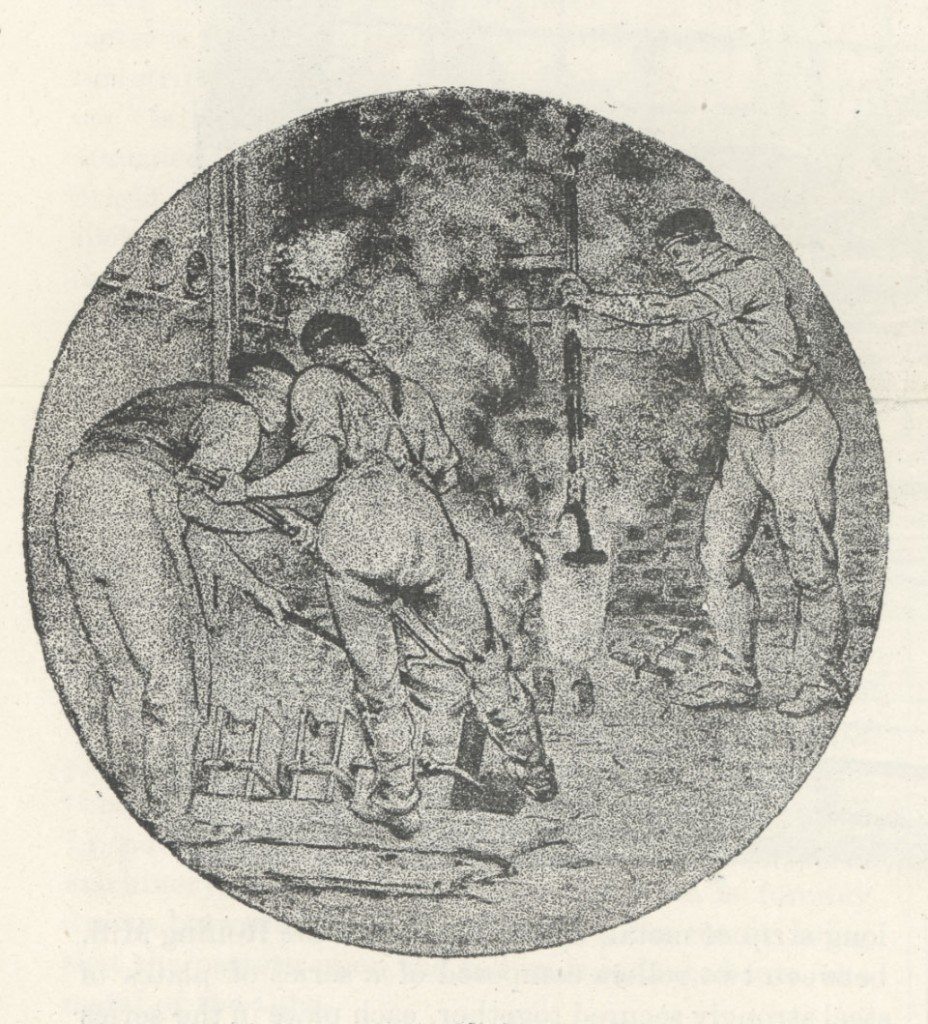

Image: Brass-making at Messrs R W Winfield and Co. in 1887 from “The Homes of our Metal Manufactures. Messrs R W Winfield and Co’s Cambridge Street Works & Rolling Mills, Birmingham”, in Martineau & Smith’s Hardware Trade Journal (Jan 31, 1887, p 9). The image shows molten brass being transported by one worker in a crucible. In the foreground the fluid metal is poured into iron moulds to create ingots which can then be passed onto the next stages of production, such as rolling or slitting. The dangers inherent in this work can be seen in the picture, not only from the heat, but also from the fumes, known as philosopher’s wool, a dense white gas of zinc oxide.

[Image from: Birmingham Central Library, Local Studies and History]

At a conference in 1872, R H Best, chandelier maker of Birmingham, stated that he knew of two of his men who, after paying their underhands, made the sum of £3.00p. His son reported, in 1905, that “On many a soldering hearth there was the sizzling of bacon and the boiling of tea for half and hour after the morning arrivals, and again as one o’clock approached, but then the aroma changed to one of chops.” As long as it did not interfere with production he turned a blind eye. Despite manufacturing chandeliers, Best’s factory was not well-lit. This was because the vibration of the machines caused the fragile mantles to break easily.

The traditional keeping of “Saint Monday” whereby workers did not return to work until Tuesday, and then made up the hours during the rest of the week, was still upheld in the brass trade until the late nineteenth century. Whilst this was not so important in small workshops, in larger foundries or factories the absence of workers in key positions held up output in the production process.

The Birmingham historian, William Hutton, writing in the late 18th century summed up the “curious art” of brassfounding as being “… less ancient than profitable and less healthful than either”. In both respects he was accurate, as brassworkers contracted pulmonary and respiratory diseases from the dust and fumes emitted in the various processes. This led one industrial historian to comment in 1866 that “Brass casters are unanimously short-lived”.

In the St Laurence Parish of Birmingham in the early twentieth century, the phenomenon of green snow was reported. This parish was home to a number of brass foundries, and illnesses of the respiratory system were rife amongst both workers and the residents who shared their streets with a large number of such establishments.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The Brass Industry and Brass Workers in Birmingham

The Brass Industry and Brass Workers in Birmingham

The Early Brass Trade

The Early Brass Trade

The Origins of the Brass Industry in the Midlands and Birmingham

The Origins of the Brass Industry in the Midlands and Birmingham

Innovation in the Midlands Brass Industry

Innovation in the Midlands Brass Industry

Brassworking Skills in Birmingham

Brassworking Skills in Birmingham

Demand for Birmingham Brass in Britain and Abroad

Demand for Birmingham Brass in Britain and Abroad

Entrepreneurship 1: Birmingham Brassfounders and the Building of the Brass House

Entrepreneurship 1: Birmingham Brassfounders and the Building of the Brass House

Entrepreneurship 2: The Birmingham Metal Company and The Birmingham Mining and Copper Company

Entrepreneurship 2: The Birmingham Metal Company and The Birmingham Mining and Copper Company

The Organisation of the Birmingham Workforce

The Organisation of the Birmingham Workforce

Working Practices and Conditions in the Birmingham Brass Industry

Working Practices and Conditions in the Birmingham Brass Industry

Trades Unions

Trades Unions

Conclusion: Further Investigation

Conclusion: Further Investigation

Glossary

Glossary