Birmingham

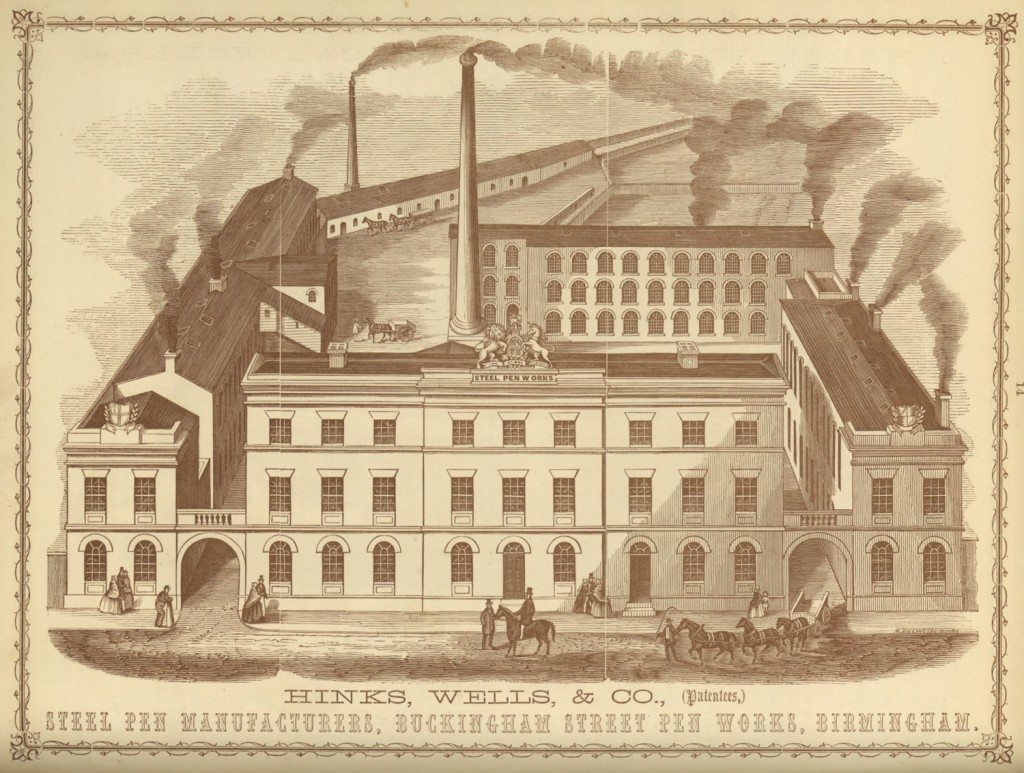

Image: Hinks, Wells & Co, Steel Pen Manufacturers, Buckingham Street Pen Works, Birmingham

Image from: The New Illustrated Directory Entitled Men and Things of Modern England, 1858

Local Studies and History, Central Library, Birmingham

BIRMINGHAM [1]

We cannot venture, in the space allotted to us, to attempt a description of all the branches of trade carried on in the great Midland Metropolis – the town which Burke denominated “The Toyshop of Europe”. The title is somewhat of a misnomer. Birmingham makes toys enough no doubt; but they are intended for the rough hands of hardworking men; not to amuse the idle hours of laughing children. Her toys are the gun, the sword, the axe, the spade, the anvil, the steam engine. Wherever useful work has to be done, wherever stubborn Nature needs to be subdued to the wants of man, wherever wild wastes are to be brought into blooming cultivation, or the bowels of the earth to be rifled of their rich and varied mineral treasures, there are to be found the ‘toys’ of Birmingham – toys in producing which her hardy sons have sweated over the glowing forge, or toiled at the swift-revolving lathe, or wielded the ponderous hammer, or plied the sharp-biting file. In her earlier days Birmingham altogether lacked the graces with which she has since be-decked herself. To use the words of her sole historian, Hutton, she was “comparatively small in her size, homely in her person and coarse in her dress – her ornaments wholly of iron from her own forge.” But even in his remote day Hutton decried the coming greatness of his adopted town. Looking to the future he exclaimed, with something of a prophetic spirit – “We have only seen her in infancy. But now her growth will be amazing, her expansion rapid, perhaps not to be paralleled in history. We shall see her rise in all the beauty of youth, of grace, of elegance and attract the notice of the commercial world. She will also add to her iron ornaments the lustre of every metal that the whole earth can produce, with all their illustrious race of compounds heightened by fancy and garnished with jewels. She will draw from the fossil and the vegetable kingdoms; press the ocean for shell, skin and coral. She will also tax the animal for horn, bone and ivory and she will decorate the whole with touches of her pencil.” The fanciful picture drawn in these glowing colours by the old antiquary has been realised to the letter. The manufactures of Birmingham are dispersed over the whole world. Wherever commerce has been established Birmingham has found a market for some, at least, of the infinite variety of her wares. In the luxurious capitals of Europe, in the vast empires of Asia, in the dense forests of Western America, in the boundless plains of Russia, in the thriving communities of Australia, in the farthest islands of the Eastern and Western Oceans, Birmingham has supplied the ever-growing wants of man, civilized or savage. The Arab Sheikh eats his pillau with a Birmingham spoon, the Egyptian Pasha takes from a Birmingham tray his bowl of sherbert, or illumes his harem with glittering candelabra made of Birmingham glass, or decorates his yacht with cunningly-designed pictures painted by Birmingham workmen on Birmingham papier mâché. The American Indian provides himself with food, or defends himself in war by the unerring use of a Birmingham rifle; the luxurious Hindoo loads his table with Birmingham plate and hangs in his saloon a handsome Birmingham lamp. The swift horsemen who scour the plains of South America urge on their steeds with Birmingham spurs and deck their gaudy jackets with Birmingham buttons. The Negro labourer hacks down the sugar cane with Birmingham machetes and presses the luscious juice into Birmingham vats and coolers. The dreamy German strikes a light for his everlasting pipe with a Birmingham steel on tinder, in a Birmingham box. The emigrant cooks his frugal dinner in a Birmingham saucepan over a Birmingham stove and carries his little luxuries in tins stamped with the name of a Birmingham maker. But we need not continue the catalogue. It is impossible to move without finding traces of the great hive of metal workers – the veritable followers of Tubal Cain. The palace and the cottage, the peasant and the prince, are alike indebted for necessaries, comforts and luxuries, to the busy fingers of Birmingham men. The locks and bolts which fasten our doors, the bedsteads on which we sleep, the cooking vessels in which our meals are prepared, the nails which hold together our shoes, the tips of our bootlaces, the metal tops of our inkstands, our curtain rods and cornices, the castors on which our tables roll, our fenders and fire-irons, our drinking glasses and decanters, the pens with which we write and much of the jewellery with which we adorn ourselves, are made at Birmingham. At home or abroad, sleeping or waking, walking or riding, in a carriage or on a railway or steamboat, we cannot escape reminiscences of Birmingham. She haunts us from the cradle to the grave. She supplies us with the spoon that first brings our infant lips into acquaintance with ‘pap’ and provides the lugubrious ‘furniture’ which is affixed to our coffins. In her turn Birmingham lays the whole world under contribution for material. For her smiths and metal workers and jewellers, wherever nature has deposited stores of useful or precious metals, or has hidden glittering gems, there industrious miners are busily digging. Divers collect for her button makers millions of rare and costly shells. Adventurous hunters rifle for her the buffalo of his wide-spreading horns and the elephant of his ivory tusks. There is scarcely a product of any country or any climate that she does not gladly receive and in return, stamp with a new and rare value. Knowledge has endowed her with art higher than magic and it is this which enables her to take in hand substances seemingly the most worthless and by her ingenuity to convert them into articles of universal necessity, or into the most coveted appliances of the highest luxury. We have spoken at length and thus warmly – not from mere local predilections – but because Birmingham may be regarded as a microcosm of the industry of England. There are perhaps other towns which use more iron, more steel, more gold, more jewels; there are other towns compared with which Birmingham has very few factories worthy the name; there are other towns which far outstrip Birmingham in wealth and outnumber her in people; but there is no town in the world where so many trades are practised; nor is there any community which manifests more acuteness and ingenuity, which is characterised by greater industry, or distinguished by high inventive skill.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The First Manufacturing Town: Industry in Birmingham in the mid-19th Century, The New Illustrated Directory, 1858

The First Manufacturing Town: Industry in Birmingham in the mid-19th Century, The New Illustrated Directory, 1858

The Manufactures of Birmingham and Sheffield

The Manufactures of Birmingham and Sheffield

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham