Shenstone and the Creation of the Natural Landscape

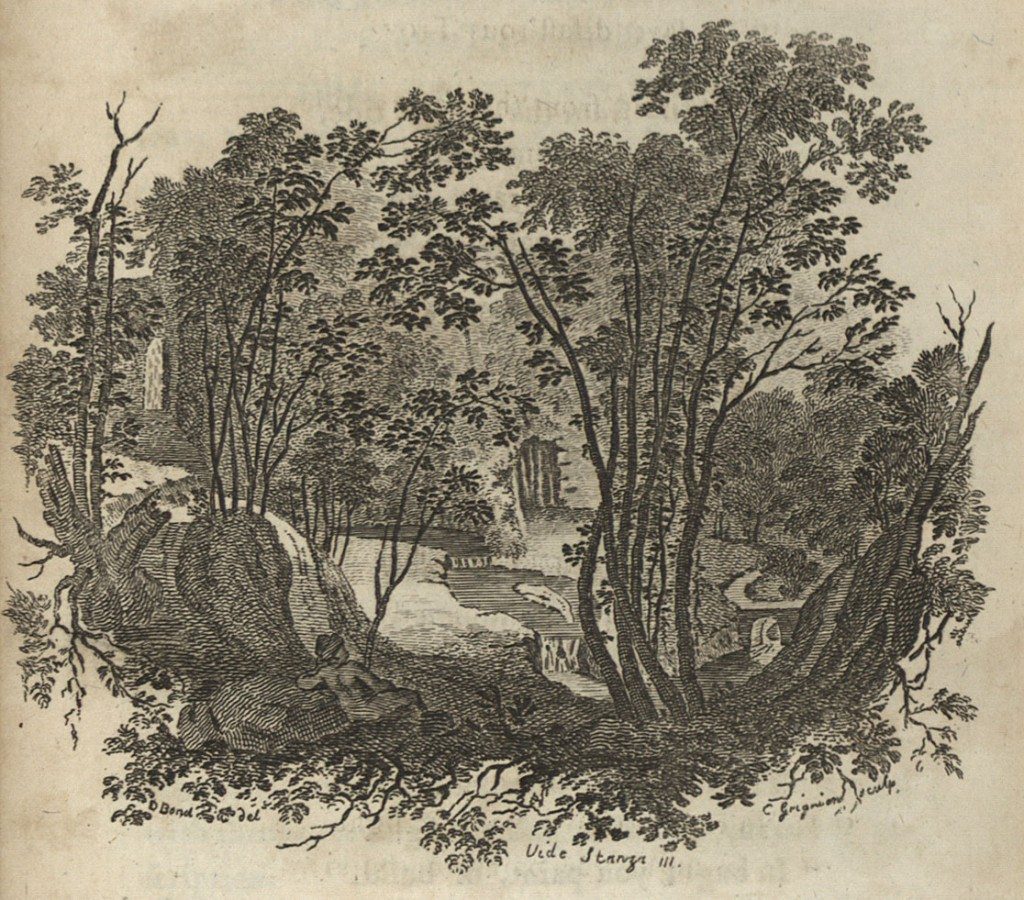

Image: This engraving represents a scene within William Shenstone’s estate at the Leasowes, possibly “Virgil’s Grove”, named after the Roman poet. It shows many of the features of Shenstone’s “natural” landscape embellished by “art”. An obelisk (or a representation of a cascade) on the left is “balanced” by another object, a bridge on the right. A winding stream with a waterfall meanders through the scene. Trees are necessary parts of the composition. A human figure – or cherub – observes in the foreground. From ‘A Description of the Leasowes’ by R Dodsley in The Works in Verse and Prose of William Shenstone, Esq., Vol. II, Second Edition (London, J Dodsley, 1765) p 320.

6. Shenstone and the Creation of the Natural Landscape

At the same time that the (wealthy) English were copying French or Dutch garden styles, they were also admiring paintings of idealized Italian landscapes by, for example, the seventeenth century Salvator Rosa and the Poussins. These landscapes, whether mild or wild, and whether with or without classical ruins or characters, were attractive to the ‘cultured’ English imagination and, with a native fondness for ‘nature’, contributed to the move away from geometric gardening and towards the more natural. Writing to Graves in 1759, Shenstone asks:

“Now you speak of our Arcadias, pray did you ever see a print or drawing of Poussin’s Arcadia? The idea of it is so very pleasing to me, that I had no peace until I had used the inscription on one side of Miss Dolman’s urn, ‘Et in Arcadia Ego.’” (Letters, pp.524-5)

This urn, a memorial to a cousin who had died of smallpox, was one of several objects placed carefully as visual and/or contemplative foci about Shenstone’s grounds. Others included: a small obelisk, a statue of a piping faun, other urns, and several inscribed seats. In his Unconnected Thoughts on Gardening (not published until after his death) Shenstone comments on many points, including the placing of objects and the influence of painters:

“In a scene presented to the eye, objects should never lie so much to

the right or left, as to give it any uneasiness in the examination.”

“No mere slope from one side to the other can be agreeable ground: The eye requires…a degree of uniformity…Let us examine what may be said in favour of that regularity which Mr. Pope exposes…for a kind of balance in a landskip; and…the painters generally furnish one: a building for instance on one side, contrasted by a group of trees, a large oak, or a rising hill on the other. Whence does this taste proceed, but from the love we bear to regularity in perfection? After all, in regard to gardens, the shape of ground, the disposition of trees, and the figure of water, must be sacred to nature; and no forms must be allowed that make a discovery of art.

And:

“I have used the word landskip-gardiners; because in pursuance of our present taste in gardening, every good painter of landskip appears to me the most proper designer.”

Shenstone has been credited with coining the term ‘landscape gardening’. A few further examples from his many, detailed Unconnected Thoughts:

“Concerning scenes, the more uncommon they appear, the better, provided they form a picture, and include nothing that pretends to be of nature’s production, and is not…Whatever thwarts [Nature] is treason.”

“Hedges, appearing as such, are universally bad. They discover art in nature’s province.”

“Water should ever appear, as an irregular lake or winding stream. Art, indeed, is often requisite to collect and epitomize the beauties of nature; but should never be suffered to set her mark upon them…Objects should indeed be less calculated to strike the immediate eye, than the judgement or well-informed imagination, as a painting.”

“Variety appears to me to derive good part of it’s effect from novelty…Ruinated structures appear to derive their power of pleasing from the irregularity of surface, which is variety: and the latitude they afford the imagination.” 7

————-

7 Unconnected Thoughts on Gardening in The Works in Verse and Prose of William Shenstone, Esq; in two Volumes, the second edition (London J.Dodsley, 1765-6) Vol. II, p 111-131.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

William Shenstone, The Leasowes, and Landscape Gardening

William Shenstone, The Leasowes, and Landscape Gardening

Introduction: William Shenstone and the Leasowes

Introduction: William Shenstone and the Leasowes

Shenstone’s Early Life

Shenstone’s Early Life

Shenstone, Poetry and Landscape

Shenstone, Poetry and Landscape

Shenstone, Rural Virtues and the Countryside

Shenstone, Rural Virtues and the Countryside

Shenstone and English Landscape Gardening

Shenstone and English Landscape Gardening

Shenstone and the Creation of the Natural Landscape

Shenstone and the Creation of the Natural Landscape

Shenstone, Landscape and Farming

Shenstone, Landscape and Farming

Shenstone’s Embellishments to the Leasowes

Shenstone’s Embellishments to the Leasowes

The Reputation of the Leasowes

The Reputation of the Leasowes

Appreciating the Landscape: Robert Dodsley and the Leasowes

Appreciating the Landscape: Robert Dodsley and the Leasowes

A “delightful Paradise”: The Leasowes Cult

A “delightful Paradise”: The Leasowes Cult

“Beauty and Simplicity”: Descriptions of the Leasowes

“Beauty and Simplicity”: Descriptions of the Leasowes

Shenstone’s Influence

Shenstone’s Influence

Shenstone and the Locality

Shenstone and the Locality

Conclusion

Conclusion