Introduction: the Severn Waterway

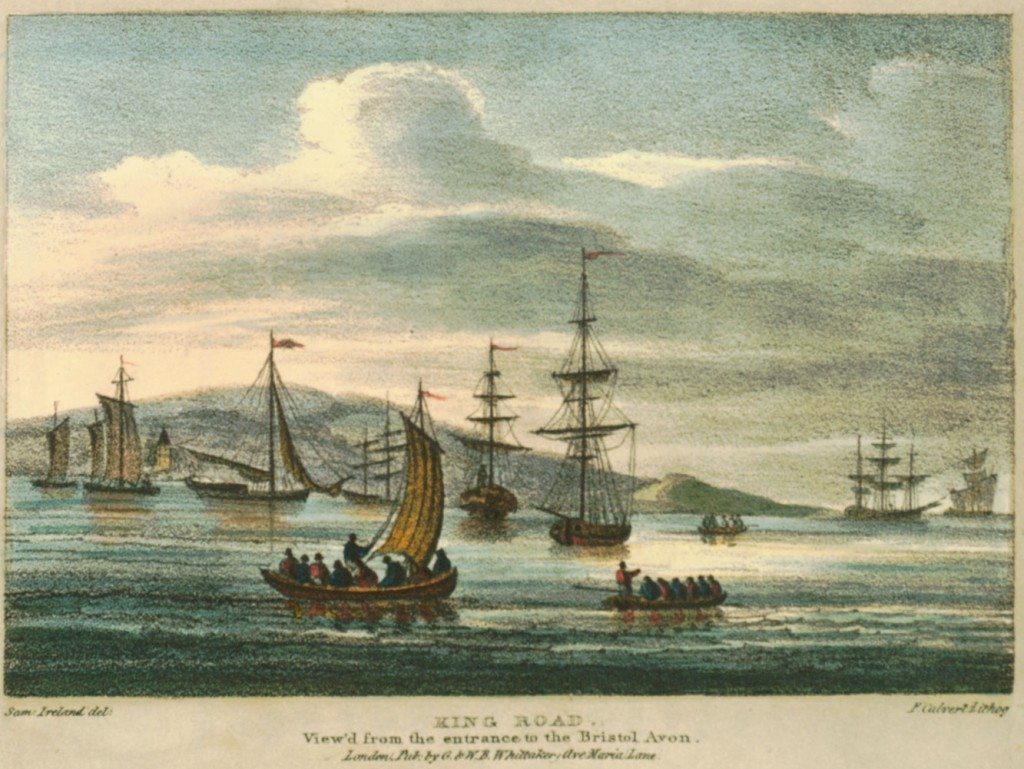

Image: King Road, viewed from the entrance to the Bristol Avon, where the Lower Avon, after running through Bath and Bristol, joins the Severn and forms the Bristol Channel. This engraving shows the mixture of river traffic and ocean going ships as the Severn meets the sea.

In 1824, a publication, Picturesque Views of the Severn, with Historical and Topographical Illustrations by Thomas Harral was published. The book, originally in two volumes was illustrated with engravings and accompanied by a detailed commentary which explored a journey from the source of the Severn in Wales, until it entered the Bristol Channel. The prints were “embellishments from designs” produced by the artist, Samuel Ireland, several years before. In some editions, the pictures are in colour. Produced for the wealthy 19th century tourist, Harral’s illustrations and text provide an account of the waterway when urban growth, commerce and industrial activity formed part of the Severn’s attractions.

The Severn rises in Wales and enters the sea via the Bristol Channel. At two hundred and twenty miles is the longest river in Britain. The name emerged from several possible roots. In Welsh, the river was called Hafren or Queen of Rivers. The British word, Sabi or Sabrin denotes muddiness or cloudiness and the Romans, deriving the name from this source, called the river Sabrina. In old maps the Severn is called Seavren, probably from Se-havren, the prefix being a reference in Welsh to the hissing sound made by streams. The word Saefyrne is first recorded as a label for the river in 706 AD (Harral, vol.1, p 3). Whatever the origins of the name, the Severn has played an important role in the history of Britain and the Midlands region.

For centuries, the river has been an agent of economic growth. As a liquid motorway, the Severn transported imports and exports to and from the interior of Britain, coastal ports and the wider world. By the 18th century it was intimately connected with the development of industry along its route. Without the Severn trade, coal, iron and other mineral resources would have been more difficult to exploit. Pastoral and arable farming flourished in the fertile and well-watered river valley. The Severn became an artery connecting central Wales, Shropshire, Worcestershire and Gloucestershire with the national and global economies.

In other respects the waterway was important. The high ground, through which the river ran, provided suitable locations for castles and settlements, as at Bridgnorth. One example of a town which developed at fords where the river could be crossed or where bridges were built was Bewdley. Shrewsbury emerged because the meandering river provided a good location for defence.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

A Journey down the Severn from Thomas Harral’s Picturesque Views of the River (1824)

A Journey down the Severn from Thomas Harral’s Picturesque Views of the River (1824)

Introduction: the Severn Waterway

Introduction: the Severn Waterway

Poetry and Visions of the River Severn

Poetry and Visions of the River Severn

The Severn and its Origins in Wales

The Severn and its Origins in Wales

Newtown to Montgomery

Newtown to Montgomery

Powis Castle to Welshpool

Powis Castle to Welshpool

Welshpool to Shrewsbury

Welshpool to Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury

Shrewsbury

The English Bridge, Shrewsbury

The English Bridge, Shrewsbury

The Welsh Bridge, Shrewsbury

The Welsh Bridge, Shrewsbury

Atcham Bridge, Shropshire

Atcham Bridge, Shropshire

The Wrekin

The Wrekin

Buildwas Bridge and the Severn Earthquake of 1773

Buildwas Bridge and the Severn Earthquake of 1773

Coalbrookdale and the Ironbridge

Coalbrookdale and the Ironbridge

Madeley, Broseley and Lilleshall

Madeley, Broseley and Lilleshall

Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth

Bridgnorth’s Economy

Bridgnorth’s Economy

Bridgnorth Castle

Bridgnorth Castle

Quatford and the nearby Landscape

Quatford and the nearby Landscape

Bewdley

Bewdley

The Wyre Forest

The Wyre Forest

Stourport

Stourport

Stourport Bridge

Stourport Bridge

Worcester

Worcester

Worcester to Upton-on-Severn

Worcester to Upton-on-Severn

Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury

Gloucester

Gloucester

Gloucester’s Economy and the Severn Trade

Gloucester’s Economy and the Severn Trade