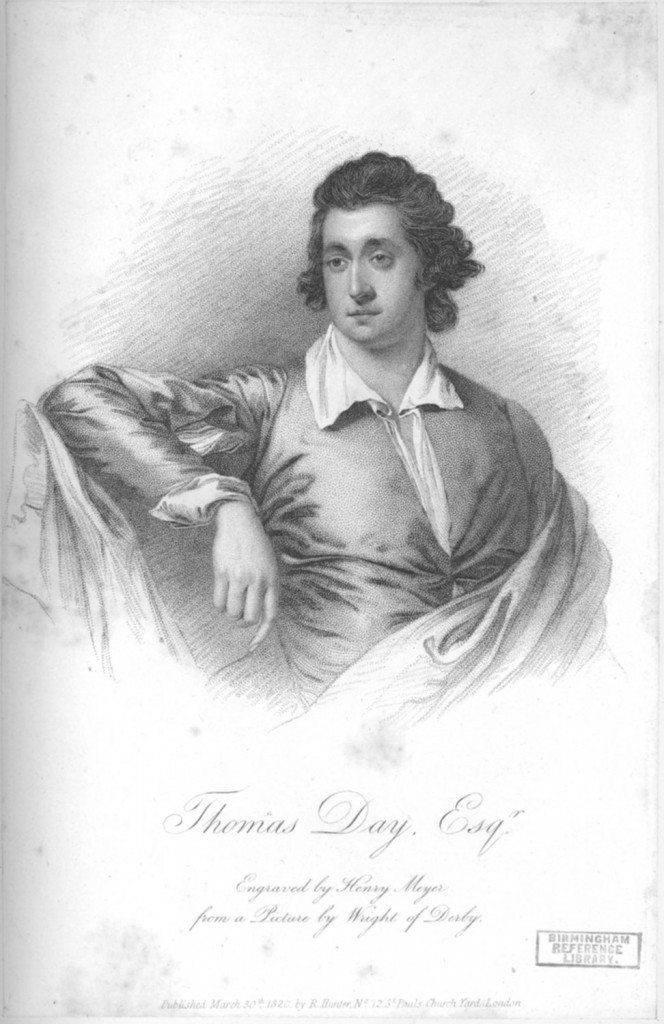

A Portrait of Thomas Day

Thomas Day: Humanitarian and Reformer

Thomas Day was born in 1748. His father was a landowner and customs official and Day was never short of money. As a boy, he showed empathy for others. He gave away his pocket money to the poor and was kind to animals. In 1764 Day went to Oxford. He was influenced by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose book Emile (1761-62) changed the way many people viewed education. Day also developed a friendship there with Richard Lovell Edgeworth.

Between 1768 and 1778 Day was preoccupied with securing a wife. Most women he met lacked the “natural” qualities he had been encouraged to seek in Rousseau’s writings. In 1769, he acquired two orphan girls, one in Shrewsbury and the other from London. They were renamed Sabrina and Lucretia and he hoped to recreate their personalities so that one of them would a suitable partner. Lucretia proved intractable; she was deemed to be “invincibly stupid” and was placed with a milliner and eventually married. He had more hope for Sabrina. In 1770 Day settled in Lichfield and became part of the Lunar network. Here he embarked on an extensive training of Sabrina. His experiments were unconventional, firing pistols at her petticoats and dropping melted sealing wax on her arms. Sabrina was eventually placed in a boarding school in Sutton Coldfield. She was not to be his wife and Day eventually left Lichfield.

In 1773, Day became a prominent opponent of slavery, publishing a best-selling poem, The Dying Negro, which went through several editions. He found happiness in his personal life, marrying Esther Milnes in 1778. She shared his ideas and was prepared to share his austere life-style. Day said “we have no right to luxuries while the poor want bread.”

In 1779 Day bought an estate in Essex, followed by one in Surrey in 1781. He participated in the politics of the day, attacking corruption, supporting the American Revolution and continuing to denounce slavery. Much of his fortune was spent on agricultural improvement and raising the living standards of his tenants. In 1783 he published Sandford and Merton, a popular book for children, a vehicle for his beliefs. In 1789, Day was killed after being thrown by his horse and was much mourned by his fellow Lunaticks for his moral courage and humanitarian commitments.

Sources and Further ReadingRowland, T.W., The Life and Times of Thomas Day, 1749-89 (Lewiston, New York, The Edwin Mellen Press, 1996)) Schofield, Robert E., The Lunar Society, A Social History of Provincial Science and Industry in Eighteenth Century England (Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1963) Uglow, Jenny, The Lunar Men: The Friends who made the Future 1730-1810 (London, Faber and Faber, 2002)