Birmingham

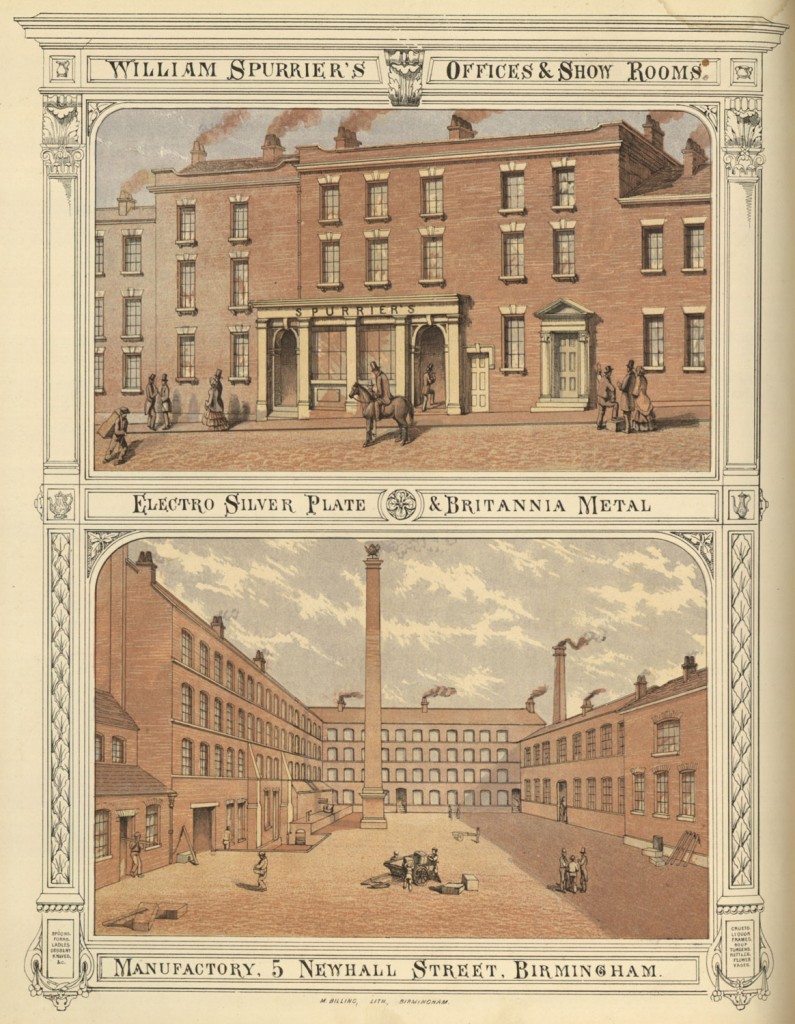

Image: William Spurrier, Electro Silver Plate Manufacturer, Birmingham

Image from: The New Illustrated Directory Entitled Men and Things of Modern England, 1858

Birmingham

Great antiquity has, without much solid ground, been claimed for Birmingham as a centre of metal manufactures. According to some fanciful writers it was from this town that the ancient Britons obtained their swords and spears and their scythe-armed chariots. “I had chariots, arms and horses,” exclaimed the British Caractacus before the tribunal of the Roman Claudius. But it does not follow that the barbarian derived his weapons from the forges of Birmingham. Authentic history does not go further back than the time of Henry the Eighth, when Leland wrote that “a great part of the town is maintained by smiths, who have their iron and sea-coal out of Staffordshire.” But the trade was then very limited. Even in Charles the Second’s time the town produced scarcely anything but tools and agricultural implements. Although there is no doubt that sword-making had been introduced before that period, yet it had not been developed into a staple manufacture. Before the middle of the eighteenth century there were no manufactures in brass. Soon after these were established, glass-making was commenced. It was followed by papier mâché; then came jewellery, then steel pens and so on by rapid strides the town accumulated in its workshops, either by creation or adoption, the numerous trades which have now become peculiarly its own. The first great impulse given to Birmingham was the substitution of coal for wood in the smelting of iron. The application of steam as a motive power was the next important step towards prosperity, although communities other than Birmingham have received most benefit from the steam engine. When it was ascertained that a machine driven by steam, would with unerring certainty and at wonderful speed, make a yard of calico or a ball of cotton, the multiplication of these products became a simple question of demand. If a manufacturer wanted to make more calico or more cotton, he had simply to set up more spindles and he was at once enabled indefinitely to extend the amount of his production. Here the steam-engine was essential; it superseded all other motive power; the trader was able to estimate with certainty the exact measure of assistance it could afford him – he could adjust his means to the designed end with mathematical accuracy. But in Birmingham steam machinery has never been more than an auxiliary force. In some trades it is still altogether dispensed with; in others it is able to do only a small portion of the work; in none does it altogether supersede skilled labour. Large numbers, probably the majority, of Birmingham workmen are employed in their own homes, or in little shops not large enough to hold more than four or five men. These artisans depend chiefly upon skilled hand labour; either they make parts of articles only, or if they find it necessary to have recourse to the aid of steam to facilitate their operations, they hire a room through which a shaft, driven by steam power, is made to pass. The result of this arrangement is that Birmingham in some measure disappoints the visitor who expects to see huge factories like those of the north, their long plain fronts pierced with hundreds of windows, cold and hard by day, but at night emitting a thousand streams of light. There are, it is true, a few factories in Birmingham which may vie with any the world can show, but these are very few; and as we have previously said, the major portion of the work is performed in small shops, or not infrequently in the garrets of houses. The stranger who desires to form an adequate idea of the industry of the great iron district should station himself on a dark night on the railway viaduct which rises above some of the business streets of the town. Beneath him and seemingly for miles around, he will observe thousands of twinkling points of fire, indicating the spots where industrious artisans are engaged in fashioning articles of Birmingham manufacture. As he travels slowly into Staffordshire he will mark before him and on every side, an endless range of houses and workshops similarly illuminated, until he reaches the lofty hill crowned by the ruins of Dudley Castle, some seven miles distant. Standing on this hill and looking over the great mineral basin which spreads out its ample breadth below, he will behold a sea of fire, leaping up from the countless pits and forges incessantly employed in yielding coal and ironstone and in converting the latter into the metal which under the hands of skilful artificers becomes to the labouring world more valuable than the finest gold. Fringing the edge of the great valley, he will perceive a broad band of light – the combination into one grand illumination of the tiny sparks that floated beneath and around the railway viaduct of Birmingham. Such a journey and only such a journey will enable a stranger to comprehend the vast extent if midland industry; to understand the gigantic labour bestowed on the conversion and adaptation of metals and to estimate at its proper rate the immense benefit conferred upon England and upon the world by the skill and capital engaged in developing and manufacturing the exhaustless stores of mineral wealth which lie hidden under the coal and ironstone strata surrounding the midland metropolis.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The First Manufacturing Town: Industry in Birmingham in the mid-19th Century, The New Illustrated Directory, 1858

The First Manufacturing Town: Industry in Birmingham in the mid-19th Century, The New Illustrated Directory, 1858

The Manufactures of Birmingham and Sheffield

The Manufactures of Birmingham and Sheffield

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham

Birmingham