Cartouches

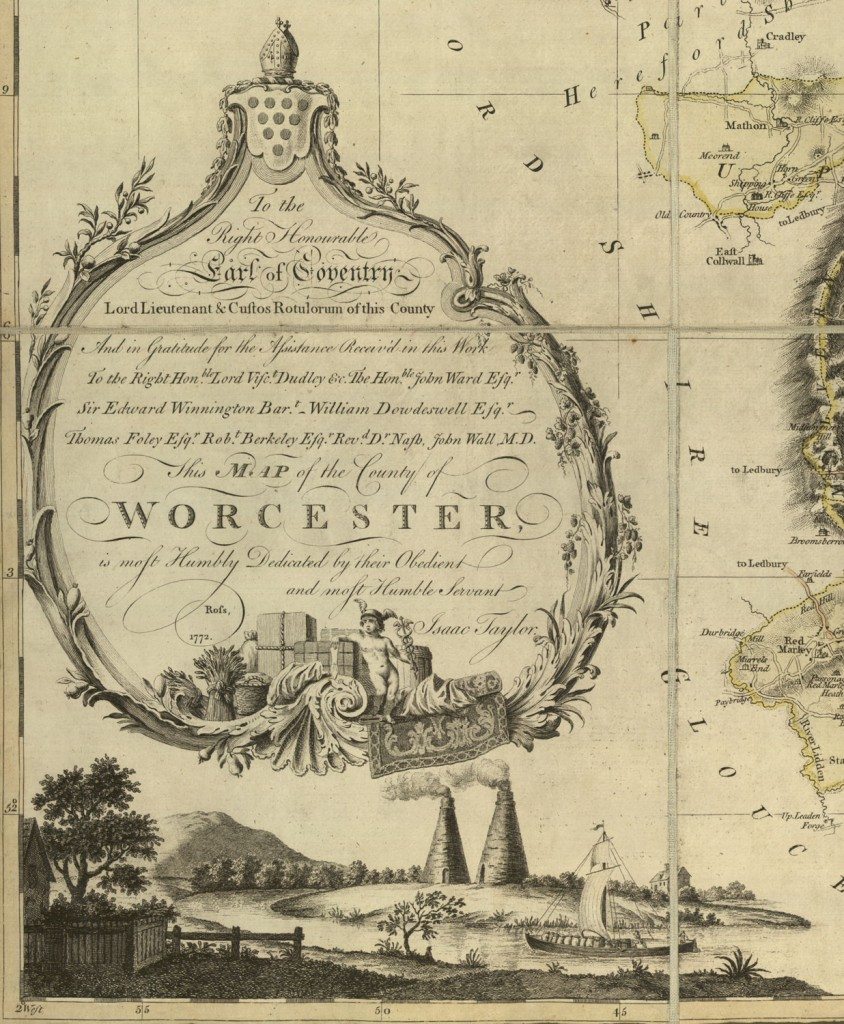

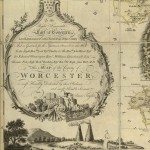

Image: Cartouche from 1772 map of Worcestershire. Fruit is important to the agriculture of Worcestershire, and fruit of various kinds entwine the surrounds of the dedication. Below are the River Severn, important for transport, kilns, and a typical landscape for Worcestershire with hills and trees.

Image from: Local Studies and History, Birmingham Central Library

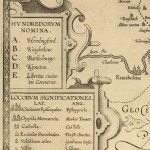

The oldest English maps were not a continuous survey, as in the modern Ordnance Survey, but followed the boundaries of the county. This meant that there would be a significant amount of white space, which was used for various purposes. If the map was sponsored by a patron, or if the map-maker hoped it would be, then the names or the coats-of-arms might be included. The key would fit in one of the corners, rather than in a border as nowadays. The orientation, and scale, would usually fit in another corner.

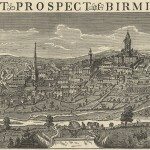

John Ogilby’s road-maps incorporated decorative cartouches at the top of the page; some with coats-of-arms, some with scenes of country life, for example hunting, or a shepherd and shepherdess with sheep. As towns grew in size, map-makers tried to appeal to a wider audience. Many county maps and town-plans of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries have insets showing miniature prospects of the most important towns, or the important buildings in a town, usually churches. Sometimes the title of the map would appear as if engraved on a plaque, surrounded by leaves. People were not usually shown. Maps of counties might include an illustration of the major agriculture or industries.

Another example of a cartouche from James Sherriff’s 1798 map of the area for 25 miles around Birmingham, serves as the introductory image for Maps and Map Making: the West Midlands Experience.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

Maps and Map Making: the West Midlands Experience

Maps and Map Making: the West Midlands Experience

Early Warwickshire Maps

Early Warwickshire Maps

The First Road Maps, John Ogilby, 1697

The First Road Maps, John Ogilby, 1697

William Westley’s Plan of Birmingham, 1731

William Westley’s Plan of Birmingham, 1731

William Westley’s Prospect of Birmingham, 1732

William Westley’s Prospect of Birmingham, 1732

Birmingham in 1751

Birmingham in 1751

Keys and Explanations

Keys and Explanations

Keys and Explanations

Keys and Explanations

Canal Maps

Canal Maps

Birmingham and the Country Around, 1798

Birmingham and the Country Around, 1798

Cartouches

Cartouches

Birmingham in 1810

Birmingham in 1810

Tithe Maps

Tithe Maps