Franklin and Baskerville: Literary Tastes

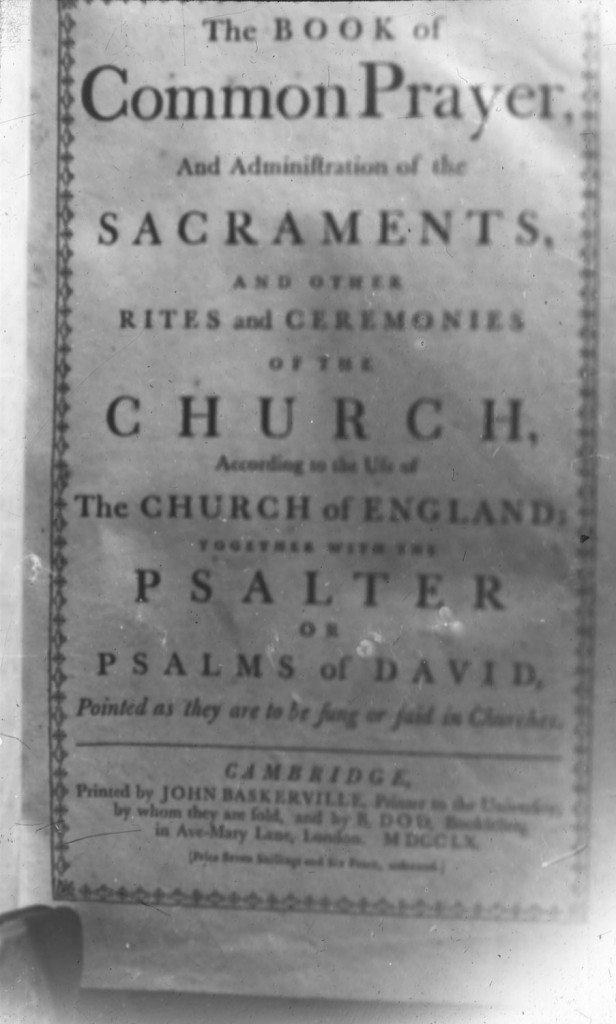

Image: Title Page from The Book of Common Prayer, printed by John Baskerville for Cambridge University, 1760. It used a type size “calculated for people, who begin to want Spectacles but are ashamed to use them at Church.”

Image from: Local Studies and History, Birmingham Central Library

It is worth noticing that Franklin was a man of letters in the ordinary sense. He strove to develop the ability of “writing well on his Mother Tongue”. He started writing at the age of 16, providing his brother’s New England Courant with series of letters under the pseudonym of Silence Dogood. He enjoyed writing, and later he contributed widely to his own Pennsylvania Gazette and almanacs. Almost all his writings were occasional. He had to write for a particular audience, or on a particular event, quickly changing his tone and style. He created several pseudonyms and was able to vary the manner of his writing to express the imagined character of the supposed author.

On the other hand, Baskerville seems to have had little taste for letters. He was a type-founder and printer, not a scholar or a writer. This might by one of the reasons why he found it so difficult to choose books for printing. In 1757, Robert Dodsley who was deeply interested in Baskerville’s work, offered to him some ideas: “What think you of some popular French books? Gilblas, Moliere, or Telemaque?” But Baskerville clearly did not want to print what was popular.

At this time, English literature was represented by many brilliant authors – Johnson, Smollett, Goldsmith, Pope, Walpole. However, all Baskerville’s books printed as his own enterprise, were reprints. In 1761 it was proposed to him, to print an edition of Pope’s works, but this came to nothing. It is as if this self-educated man was alarmed by great contemporary authors and fashionable celebrities, and preferred Latin classics instead.

Baskerville liked Hudibras , a mock-heroic poem by Samuel Butler, 1612-1680 and for a time he had an inclination to print it in quarto, but in the end this idea was also never realized.

Franklin was much more businesslike. Impressed with the great popularity of Richardson’s Pamela, he quickly undertook a Philadelphia reprinting in 1742-44. Although this edition was not particularly successful financially, it is considered today one of the most notable productions of Franklin’s press.

By the time of their meeting, Franklin, like Baskerville, had experience in printing a classical author – in 1744 he printed Cicero’s Cato Major, or his Discourses of Old Age: with explanatory Notes. It was not undertaken for profit, but rather as a courtesy to a friend – and to all elderly readers, because he used type large enough for a person with failing eyesight to read it. Baskerville might have considered Franklin’s experience later, working on his Book of Common Prayer and using a type size “calculated for people, who begin to want Spectacles but are ashamed to use them at Church.”

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

John Baskerville and Benjamin Franklin: A Trans-Atlantic Friendship

John Baskerville and Benjamin Franklin: A Trans-Atlantic Friendship

Benjamin Franklin, Printer

Benjamin Franklin, Printer

Franklin and Typefounding

Franklin and Typefounding

Baskerville and Franklin: Status and Success

Baskerville and Franklin: Status and Success

Baskerville Type

Baskerville Type

Franklin and Baskerville: Printing Activities

Franklin and Baskerville: Printing Activities

Franklin and Baskerville: Literary Tastes

Franklin and Baskerville: Literary Tastes

Franklin and Baskerville: Religion

Franklin and Baskerville: Religion

Franklin and Baskerville: Friendship and Co-operation

Franklin and Baskerville: Friendship and Co-operation

Baskerville and the Sale of Type from his Type Foundry

Baskerville and the Sale of Type from his Type Foundry

Franklin and Baskerville: Epitaphs

Franklin and Baskerville: Epitaphs