Innovation in the Midlands Brass Industry

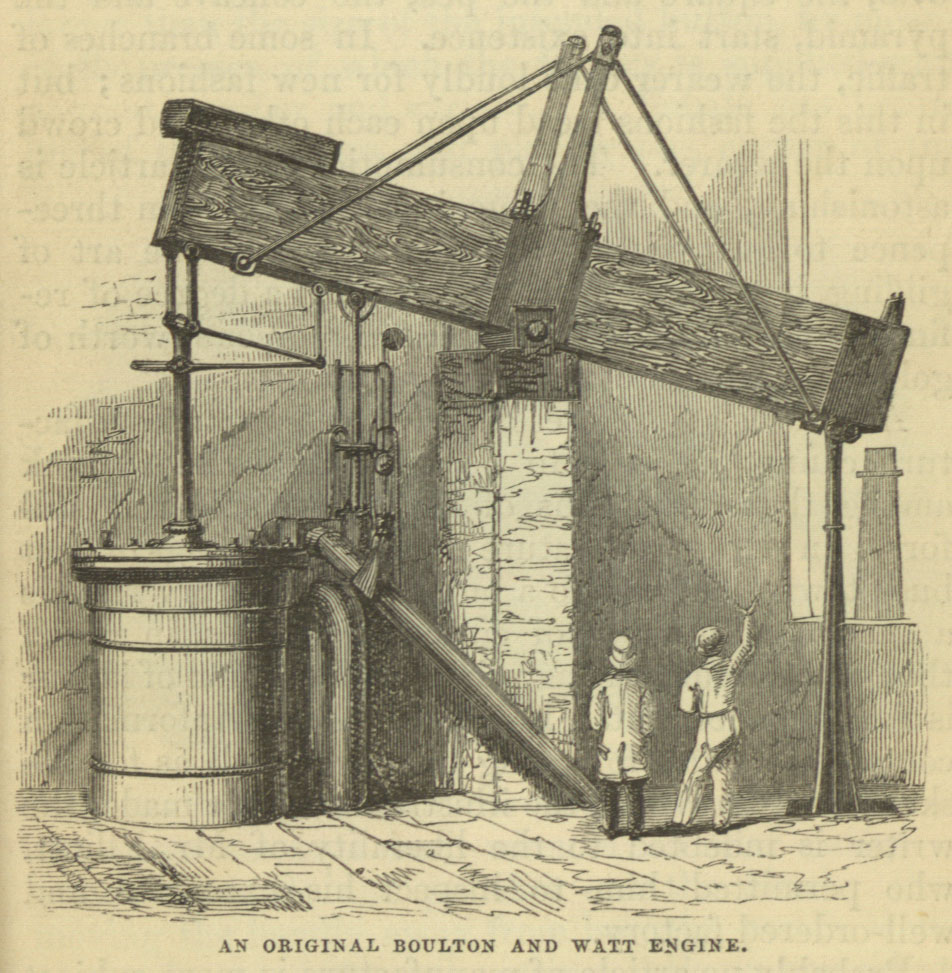

Caption: An original Boulton and Watt Engine from The Useful Arts and Manufactures of Great Britain, second part (London, SPCK nd), p 31. This engine of 100 horse power was installed at the Fazeley Street Rolling Mills in Birmingham at the end of the 18th century to provide the energy to drive rolling mills which turned cast plates of brass into sheets. The author of the article accompanying the image, written some sixty years after the installation of the machine, wrote:

“The beam is of massive timber, and its vibrations are accompanied with a loud cracking noise, which would seem to indicate want of strength and stability; but the writer was informed that the noise has always accompanied the working of the beam, and that some thirty years ago an iron beam was got ready to supply the place of the wooden one, which it was thought could not last much longer. And yet this curious and excellent engine still stands, as it were, a monument to the genius of the great improver of the steam engine.”

[Image from: Birmingham Central Library, Science and Technology]

3. Innovation in the Midlands Brass Industry

Turner’s Brass House on Coleshill Street was established in 1740 and in 1767, the first Birmingham patent was granted to William Chapman for “Refining copper and manufacturing brass and brass wire.” In 1769 the process of producing brass articles by means of stamp and die was introduced. A patent for a stamped brass foundry was granted to John Pickering, a London gilt toymaker on the 7th March 1769. This process was adopted by Richard Ford in his Birmingham factory. David Harcourt took out the patent in 1835 for the first automatic press and almost a hundred years later the same machine was still in use in the family’s manufactory.

Until the nineteenth century casting was the usual method used by brassfounders, which involved pouring molten copper alloys into moulds. Braziers, a separate trade, wrought goods by hand from sheet brass. Both had their own guilds or companies established in 14th century London. Birmingham was not a guild town, and, therefore attracted workers and entrepreneurs from far and wide, many of whom brought certain skills with them – from the chain and nailmaking trades of the Black Country for instance. Each item required a pattern from which copies were cast and moulds were made by packing sand around the pattern in a rectangular wooden or iron frame, which was made in two halves. Molten metal was poured through a runner (a channel cut through the sand) and smaller channels, called risers, were cut to enable hot air and gasses to escape as the molten metal reached the mould. A fettler was responsible for removing the stem from the mould when cooled, and all roughness was filed off.

The tools of the trade were inexpensive and easy to obtain – a lathe, vice and a few hand tools were the stock-in-trade of many small workshops. The “manufacturer” resided in the front part of his residence whilst upstairs and behind the house he “treddled the turning lathe, and, begirt with apron, examined the work, tied it up, made out the invoice and sent the finished work off to its destination”.

The bright, yellow, newness of brass articles was achieved by pickling it in acid – a dangerous aspect of the trade – and the process of “dead dipping” was discovered by accident when, in 1832, a worker at David Malins’ foundry left a quantity of articles in the cleaning solution (dipping) overnight. The strong acid (or pickling process) turned the items a dull, frosted yellow, but after burnishing and lacquering the desired effect was achieved. Burnishing was carried out by steel burnishers and the articles then passed through acid before being rinsed and dried out in a warm box of sawdust. The final process of lacquering covered the finished articles with a transparent varnish, which could contain dissolved seed lac to which was added “tumeric, dragon’s blood or sandalwood” to impart the colour. The source of the dragon’s blood is not given in any of the histories of the trade!

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The Brass Industry and Brass Workers in Birmingham

The Brass Industry and Brass Workers in Birmingham

The Early Brass Trade

The Early Brass Trade

The Origins of the Brass Industry in the Midlands and Birmingham

The Origins of the Brass Industry in the Midlands and Birmingham

Innovation in the Midlands Brass Industry

Innovation in the Midlands Brass Industry

Brassworking Skills in Birmingham

Brassworking Skills in Birmingham

Demand for Birmingham Brass in Britain and Abroad

Demand for Birmingham Brass in Britain and Abroad

Entrepreneurship 1: Birmingham Brassfounders and the Building of the Brass House

Entrepreneurship 1: Birmingham Brassfounders and the Building of the Brass House

Entrepreneurship 2: The Birmingham Metal Company and The Birmingham Mining and Copper Company

Entrepreneurship 2: The Birmingham Metal Company and The Birmingham Mining and Copper Company

The Organisation of the Birmingham Workforce

The Organisation of the Birmingham Workforce

Working Practices and Conditions in the Birmingham Brass Industry

Working Practices and Conditions in the Birmingham Brass Industry

Trades Unions

Trades Unions

Conclusion: Further Investigation

Conclusion: Further Investigation

Glossary

Glossary