Johnson and the Midlands Landscape

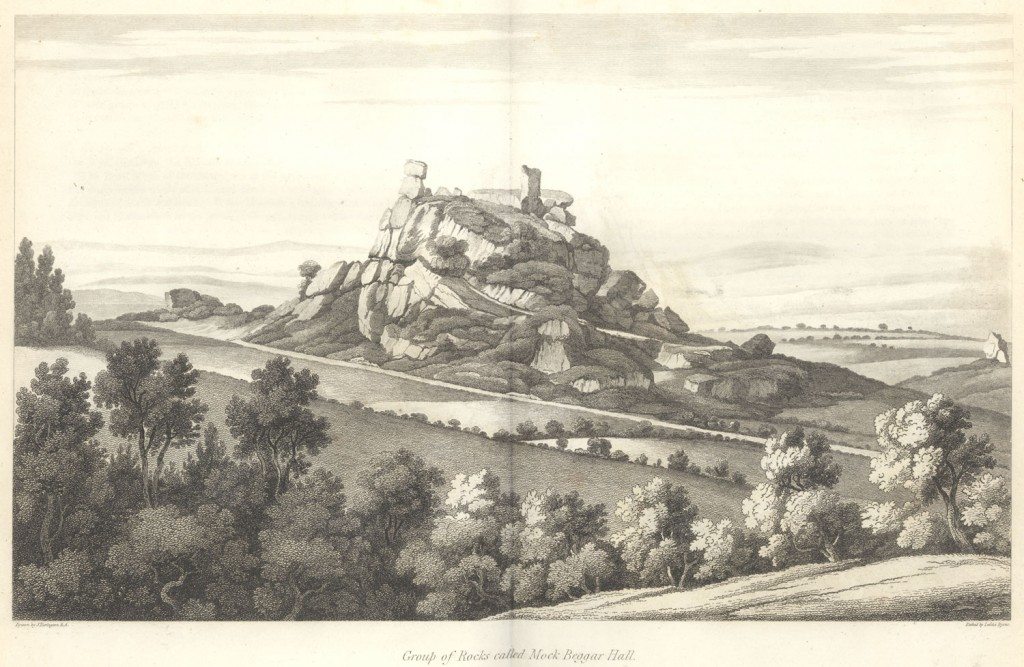

Image: Group of Rocks called Mock Beggar Hall, Derbyshire. Visitors to Derbyshire, such as Samuel Johnson were struck by the grandeur of the landscape. Rev Daniel Lysons and Samuel Lysons, Magna Britannia, being a Concise Topographical Account of the Several Counties of Great Britain, Volume the Fifth containing Derbyshire, (London, T Cadell and W Davies, 1817)

Image from: Local Studies and History, Birmingham Central Library

Throughout his writings Johnson always insisted that knowledge attained from observation and personal experience had to be added to that gained from books, for example in Rambler 177 (v: 168), Adventurer 85 (ii: 412). In Adventurer 115, Johnson states that it is inadmissible to “teach what we don’t know” and irresponsible to “instruct others while we are ourselves in want of a means of communication of acquired knowledge in a pleasurable way”.

From the mid 1760s, Johnson made yearly visits to Birmingham, Lichfield, Derby and Ashbourne which he describes in his letters. On 3 July 1771 he wrote: “Last Saturday I came to Ashbourne”, and dismissing the discomforts of travelling, he proceeds to describe the beauties of his “native plain”, with spirited vigour at the sight of the Staffordshire canal:

I crossed the Staffordshire canal one of the great efforts of human labour and human contrivance, which from the bridge on which I viewed it, passed away on either side, and loses itself in distant regions uniting waters that Nature had divided, and dividing lands which Nature had united. (Letters, i: 366-7).

Apart from his succinct and vibrant style, the description betrays a bond with his Midlands. It also demonstrates his sense of pride in the progress that was taking place in the region. The Staffordshire Canal ran from the mouth of the River Derwent in Derbyshire to near Stone in Staffordshire as part of the Grand Canal from the Trent to the Mersey. In 1758 the Derbyshire-born canal pioneer James Brindley surveyed a route which he revised again in 1763-4. The Gentleman’s Magazine featured a plan of it in the year of Johnson’s travel to Derbyshire (GM July 1771, 286), and it was reproduced in Powell’s edition of the Letters (i: 256-7).

Johnson’s description creates a vivid image of the scene. Visible and lasting man-made structures, like lines stretched between two points prescribing security and direction, the bridge and the canal resembled finite pieces of space brought together. Separated from Nature’s whole, they were “uniting water that Nature had divided, and dividing lands which Nature had united”. Johnson’s affinity to nature may have been reinforced by his early years in Staffordshire and his visits to Derbyshire, the latter being one of the English countries which combined industry, agriculture and the type of mountainous scenery that was attracting the 18th century traveller.

The Derbyshire historian Henry Kirke wrote, “we might claim Johnson as a Derbyshire man”. Johnson’s father and grandfather came from Cubley, Johnson married Elizabeth Porter at St Warburgh church in Derby on 9 July 1735 and after her death in 1752 the most plausible candidate for the role of his second wife was the Derbyshire lady, Hill Boothby. Johnson may have contributed to the Derby Mercury, which began its publication in 1732 and was one of the most sophisticated provincial newspapers. Johnson’s Diary of the 1774 tour of England and Wales with the Thrales begins with an account of Chatsworth, Matlock, Ashbourne, Derby and Dovedale. Although Dovedale did not meet his expectations, his observation that “he that has seen Dovedale has no need to visit the Highlands”, suggests that the mountains and rivers of Derbyshire did not pale into insignificance beside the Scottish scenery which he had witnessed the previous year with Boswell on his tour of Scotland.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The occurrences of common life: Samuel Johnson, Practical Science and Industry in the Midlands

The occurrences of common life: Samuel Johnson, Practical Science and Industry in the Midlands

Johnson: Observation and Enquiry

Johnson: Observation and Enquiry

Johnson and Science

Johnson and Science

Johnson, the Natural World and Industry

Johnson, the Natural World and Industry

Johnson, Bridges and John Gwynn

Johnson, Bridges and John Gwynn

Johnson and Practical Improvement: Iron

Johnson and Practical Improvement: Iron

Johnson and the Midlands Landscape

Johnson and the Midlands Landscape

Johnson and Derby Porcelain

Johnson and Derby Porcelain

Johnson and Silk Production in Derby

Johnson and Silk Production in Derby

Johnson in Birmingham

Johnson in Birmingham

Johnson, John Wyatt and Lewis Paul: Improvements to Cotton Spinning

Johnson, John Wyatt and Lewis Paul: Improvements to Cotton Spinning

Johnson, the Society of Arts and the Transformation of the Cotton Industry

Johnson, the Society of Arts and the Transformation of the Cotton Industry

Johnson and John Baskerville

Johnson and John Baskerville

Johnson, John Taylor and Henry Clay

Johnson, John Taylor and Henry Clay

Johnson and Matthew Boulton

Johnson and Matthew Boulton

Johnson: “a longer stay”

Johnson: “a longer stay”