Natural History in Greene’s Museum

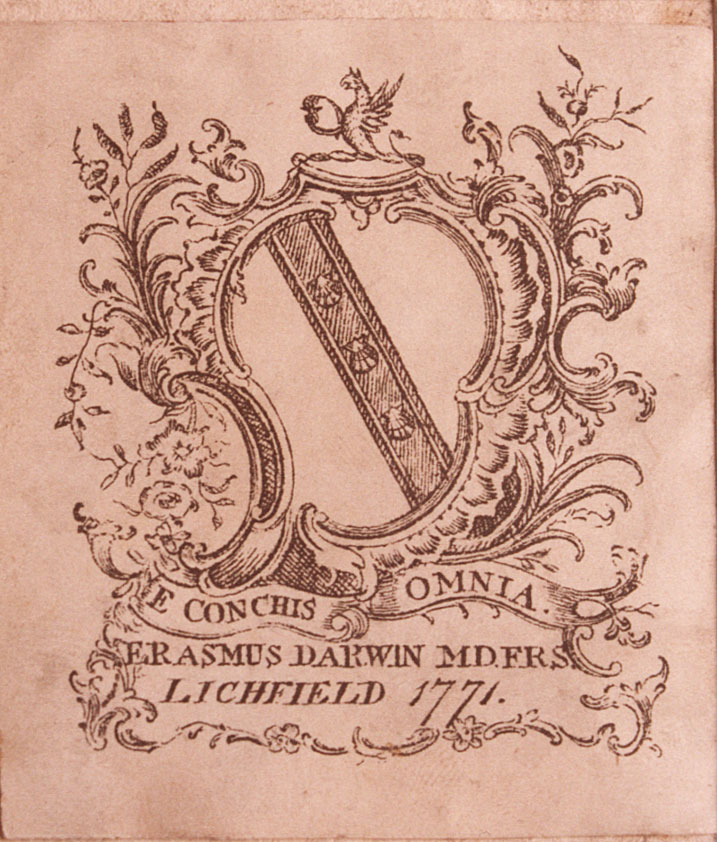

Image Erasmus Darwin’s bookplate. Darwin added a Latin motto to the family arms of three scallop shells, E conchia omnia, which translates as Everything from shells. The motto expressed Darwin’s belief that all life was descended from a single ancestor. Shells provided one of the most important collections of natural objects in the museum and Darwin’s scientific investigations benefited from Greene’s collection.

Image from: Erasmus Darwin House, Lichfield. Photograph: David Remes (2003)

The second significant group of materials consisted of various specimens of natural history which directly corresponded to Erasmus Darwin’s scientific interests. Darwin lived in Lichfield from 1756 to 1781 and the spectacular shells in the museum might have added something to Darwin’s inspiration for his famous motto “Everything from Shells”. Many of them were probably donated by Sir Ashton Lever (1729-1788) of Manchester, who himself was a famous collector of natural objects. All three catalogues of Greene’s museum are dedicated to Lever, ‘from whose noble repository some of the most curious of the rarities were drawn’.

Sir Ashton Lever began his collection about 1760 with seashells. Gradually it became one of the richest private collections of natural objects, including live animals. The first public display took place in April 1766, in Manchester. Following its success, Lever’s museum opened to the public at Alkrington Hall near Manchester in 1771.

In 1774, Lever moved to London, and next year his Holophusicon opened to the public in Leicester Square. Captain Cook was so impressed by Lever’s collection that he gave his Australian items to the museum. It became the first place in Europe where Australian specimens were displayed. The style of Greene’s dedications to Ashton Lever suggests their mutual sympathy and close friendship: “To you, my kind friend, by whose encouragement I was instigated, and by whose good offices I was enabled, to commence Virtuoso, I, once more, dedicate a descriptive catalogue of the Lichfield Museum.” (1782). Finally, in 1786, the dedication described Ashton Lever as “illustrious and generous Benefactor immortalized by his own matchless Museum”.

Many of the well-known scientists of the time gradually appeared among Greene’s correspondents, friends and benefactors. The third edition of Greene’s Catalogue was dedicated, as well as to Ashton Lever, to “Mr Pennant, immortalized by his various, faithful, and splendid publications, in Antiquities and Natural History”. Thomas Pennant (1726-1798), the author of British Zoology and A Tour in Wales was one of the leading naturalists of the 18th century. As a Fellow of the Royal Society, he was probably involved in the decision to send HMS Endeavour to the Pacific in 1768. A close friend of Joseph Banks, later he included the information received from Banks about Australian fauna in his History of Quadrupeds (1781) and the fourth volume of his Outlines of the Globe (1798).

In the catalogue of 1786, Daines Barrington (1727-1800) is mentioned among the benefactors. A lawyer, antiquary and naturalist, he was particularly known for his observations of birds, which were described in his books Experiments and Observations on the Singing of Birds and Essay of the Language of Birds (1791). In 1781 he attempted to explain the origin of fossils.

On a copy of the second edition of the catalogue (1782), which is preserved at the William Salt Library, Stafford, there is Greene’s autograph: “From R.Greene to his worthy and much esteem’d Friend and benefactor Mr J.White, London”. Through Rev. John White, both Richard Greene and Ashton Lever knew his brother, the celebrated naturalist Gilbert White (1720-1795), the author of the Natural History and Antiquities of Selbourne (1788), which consists of letters written to Thomas Pennant and Daines Barrington. Gilbert White also collected natural specimens, and generously gave some to both museums.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

A Window on the World: Richard Greene’s Museum of Curiosities in Lichfield

A Window on the World: Richard Greene’s Museum of Curiosities in Lichfield

Richard Greene and 18th Century Museums

Richard Greene and 18th Century Museums

British Antiquities in Greene’s Museum

British Antiquities in Greene’s Museum

Natural History in Greene’s Museum

Natural History in Greene’s Museum

Curiosities in Greene’s Museum

Curiosities in Greene’s Museum

Curiosities in Greene’s Museum

Curiosities in Greene’s Museum

Samuel Johnson and Greene’s Museum

Samuel Johnson and Greene’s Museum

Erasmus Darwin, the Lunar Society and Greene’s Museum

Erasmus Darwin, the Lunar Society and Greene’s Museum

Joseph Wright of Derby and Greene’s Museum

Joseph Wright of Derby and Greene’s Museum

Matthew Boulton, John Whitehurst, Josiah Wedgwood and Greene’s Museum

Matthew Boulton, John Whitehurst, Josiah Wedgwood and Greene’s Museum

The Reputation and Importance of Greene’s Museum

The Reputation and Importance of Greene’s Museum