Priestley and the Church of England

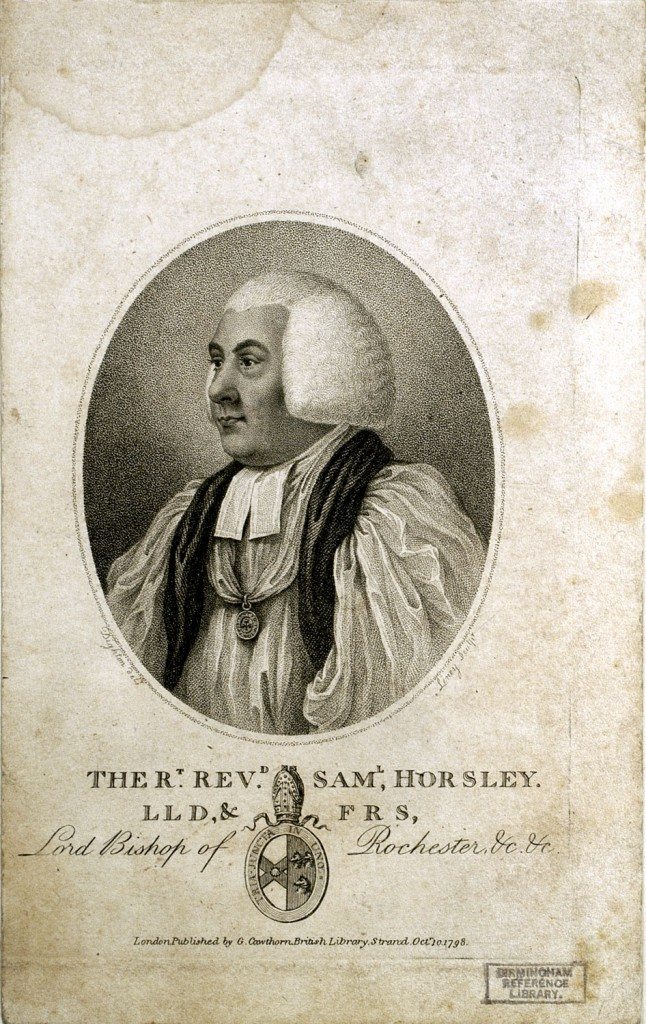

Image: Bishop Samuel Horsley, one of Priestley’s main Anglican opponents.

Image from: Birmingham City Archives, Priestley Collection by Samuel Timmins.

In his religious views Priestley attracted most opposition and almost hatred from the Established Church, the Church of England. Some of his most vociferous opponents were churchmen. William Hutton even cynically claimed that they could make their names from attacking Priestley. “To dispute with the doctor was deemed the road to preferment. He had already made two bishops, and there were still several heads, which wanted mitres, and others who cast a more humble eye upon tithes and glebe lands.20Hutton had a point; Priestley was following in the footsteps of the 17th Quakers by threatening the livelihoods of Anglican churchmen. Paul Langford called Priestley the high priest of rational dissent21, which, as Roy Porter has explained, was the natural conclusion of “the searchlight of reason and standard of debate”22. Despite the illusion of religious toleration, after the misnamed Toleration Act of 1689, the provisions of the Test and Corporation Acts forced Dissenters into becoming outsiders. Priestley, as always, took this belief of rational dissent to its most logical conclusion. He became a full-blown Socinian, later known as Unitarian, denying the divinity of Jesus Christ and viewing the worship of Christ as idolatrous. It was no wonder that he attracted so much opposition from churchmen.

For over a hundred years, religious tensions had been simmering between Anglicans and Dissenters, despite the 1689 Toleration Act. In fact, the term toleration was something of a misnomer. The preamble to the Act states that it was an act for ”some ease to scrupulous consciences in the exercise of religion”23. The emphasis should be on the word some. The Act repealed neither the Act of Uniformity nor the Clarendon Code and merely exempted Dissenters from any of their penalties. During the passage of the Bill through the Commons, one Whig was heard to remark dryly, that “the Committee, though they were for Indulgence, were for no Toleration.”24 Furthermore, the aforementioned exemptions were only granted to Trinitarian Dissenters, explicitly excluding anti-Trinitarians (Socinians or Unitarians), Roman Catholics, Jews and even atheists.

Unitarians had even more cause for grievance after the 1698 Blasphemy Act was passed. This was specifically directed against any who denied the Trinity and a second offence could even result in three years imprisonment.25 As a result of this, it could be argued that the Unitarians gradually replaced the Quakers as the Dissenting whipping boys of the established Church during the course of the eighteenth century.

The Quakers had slowly lost their reputation for religious fervour over the course of the eighteenth century and had acquired a reputation for passiveness. They concentrated their attention on the removal of the burden of paying tithes by pressurising successive governments throughout the century by the highly organised compilation of the Great Books of Sufferings.26 For the Unitarians, however, any grievances were made even harder to bear when they were refused access to civil and military offices, and therefore any real political influence, under the Test and Corporation Acts. It was their agitation for the repeal of these acts, which would result in national and local tensions in Birmingham immediately prior to the 1791 Riots.

Although always mentioned together when discussing the dissenters’ grievances, the Test and Corporation Acts were actually slightly different. Together, they presented formidable obstacles to eighteenth century Dissenters taking their places in society and ever fulfilling their full potential. The Corporation Act of 1661 required all holders of municipal offices to take the Oath of Allegiance and Supremacy, abjure the Solemn League and Covenant and finally to take communion in the Church of England. The last requirement effectively excluded all conscientious Dissenters from holding civil office. In practice, the effects of this could prove much worse as it was still possible for Dissenters to be elected to office by Anglican colleagues, whether in spite or not, and then to be fined for failing to serve.27 The first Sampson Lloyd had had this very problem in 1696-7, when he was pricked High Sheriff for the county of Herefordshire. He turned for help to his brother-in-law Ambrose Crowley junior, who was at the height of his wealth from his iron trade in London and had acquired some influence as a member of the Court of Common Council of the City of London. It was only through a lot of hard work that he was able to get Sampson discharged from the duty.28

20 Jewitt ed., The Life of William Hutton quoted in Smith, p12

21 Langford, Paul, The Eighteenth Century (Oxford University Press, Oxford) p 99

22 Porter, Roy, Flesh in the Age of Reason (Allen Lane, 2003) p 363-4

23 Coffey, op cit, p 199

24 Ibid

25 Coffey, op cit, p 200

26 For details of religious tensions against the Quakers in seventeenth-century Birmingham, see Hill, Gay, Religious Rivalries (Unpublished MA thesis, University of Birmingham, 2003).

27 Coffey, op cit, p 168

28 Lloyd, Humphrey, The Quaker Lloyds in the Industrial Revolution (Hutchinson, 1975) p 71-2

Continue browsing this section

Gunpowder Joe: Priestley’s Religious Radicalism

Gunpowder Joe: Priestley’s Religious Radicalism

Introduction

Introduction

Priestley, Subversion and 1791

Priestley, Subversion and 1791

Priestley and John Wesley

Priestley and John Wesley

Priestley and the Church of England

Priestley and the Church of England

Priestley and the Church of England

Priestley and the Church of England

Gunpowder Joe

Gunpowder Joe

Gunpowder Joe: The Reaction

Gunpowder Joe: The Reaction