Priestley’s Early Career

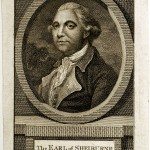

Image: The Earl of Shelburne, Priestley’s patron from 1772 to 1780

Image from: Birmingham City Archives, Priestley Collection by Samuel Timmins

After Daventry, Joseph Priestley held several posts in quick succession. Between 1755 and 1758 he ministered to a small presbyterian congregation in Needham Market, Suffolk; then he moved on to a post at Nantwich in Cheshire. In 1761 he was appointed tutor in languages and literature at the recently established Warrington Academy, and it was here that he first discovered his talent as a teacher and a populariser. The post also gave him more time and the financial wherewithal to indulge his love of natural philosophy, as experimental science was then known. His first scientific publication, The History and Present State of Electricity (1767), dates from this period, and it earned him election to the Royal Society. He also got married, taking Mary, sister of the famous ironmasters John and William Wilkinson, as his bride.

The 1760s and 1770s were the most enduringly productive decades of Joseph Priestley’s life. During these years he refined and stabilised his religious beliefs; he discovered his talent as a communicator; and, of course, he started to acquire a formidable reputation as an experimental scientist. Between 1767 and 1774 he made fundamental discoveries in the field of electrostatics and gaseous chemistry, with the result that his reputation and network of correspondents spread across the whole of Europe. He also discovered that he possessed a ready pen and began to develop the pamphlet mode of discourse and polemic that would become his hallmark.

Leisure, patrons and financial resources were the keys to his success in these years. After a further stint as a pastor ministering to the large congregation of Mill Hill chapel in Leeds (1767-1773), he had entered the service of the Earl of Shelburne in the role of librarian. The position paid £250.00 per annum and came with a house and access to a fine library and laboratory. It also provided an entrée to the highest society in the land, notwithstanding Priestley’s religious opinions which many found repugnant. Shelburne also took him on the continental Grand Tour and introduced him to some of the central figures of the European Enlightenment. He met philosophes (not to mention archbishops and bishops) who did not believe in God; men who were equally taken aback to discover that he, Priestley, did. Science and religion – or maybe we should say religion as revealed by the Roman Catholic church – did not make for easy bed fellows on the continent in these decades. However for Priestley there was no tension between his religion and his experimental activities – quite the opposite in fact. If we lose sight of the point that his science served his religion, and not vice versa, we risk gravely misunderstanding the man.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The Life and Times of Dr Joseph Priestley

The Life and Times of Dr Joseph Priestley

Introduction

Introduction

Priestley’s Origins

Priestley’s Origins

Priestley’s Education

Priestley’s Education

Priestley’s Early Career

Priestley’s Early Career

Priestley and Lavoisier

Priestley and Lavoisier

Priestley and Nonconformist Leaders

Priestley and Nonconformist Leaders

Priestley and Birmingham

Priestley and Birmingham

Priestley and Birmingham

Priestley and Birmingham