Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Travelling Salesmen

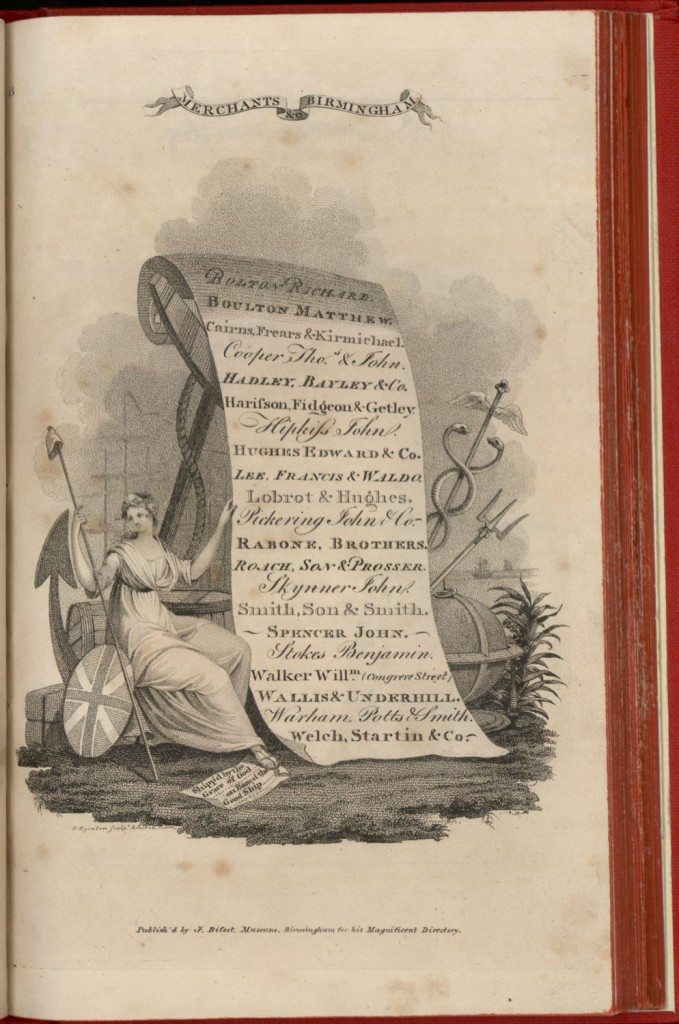

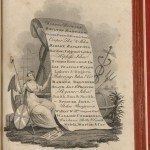

Image: Advertisement for Merchants in Birmingham. J Bisset, Bisset’s Magnificent Guide or Grand Copper Plate Directory for the Town of Birmingham…(Birmingham, Printed for the Author by R Jabet, 1808). A scroll lists the proprietors of twenty-one mercantile businesses, including Matthew Boulton resting on an anchor. There are several images linked with trade and the wider world, including ships, a globe, the winged staff of Mercury, barrels and goods wrapped for transport. Holding the scroll is the patriotic figure of Britannia. Her foot rests on another scroll which contains the message “Shipp’d by the Grace of God on Board the Good Ship”.

Image from: Local Studies and History, Birmingham Central Library

More glimpses of life on the road as a travelling export salesman come from the letters of Peter Chamot, of the hardware merchants Glover & Chamot (based in Cannon Street), who in 1763 set off for Amsterdam on the first leg of a Continental sales tour. It would be fully 12 months before he returned home. In that time he travelled through Holland, Germany, Austria, and France, visiting established and new customers.

Wherever he went, he took orders for goods which he sent back to Birmingham, checked out what the competition was doing, sent back market research, ran status checks on new customers, cajoled old customers whose accounts were overdue (being careful, of course, not to offend them so that they did not place a new order) – all the tasks generally associated with a sales job then and now, in fact.

Chamot was selling goods from Soho as well as other Birmingham manufacturers. Some of these buyers Boulton also dealt with direct. An order Chamot took in Vienna included buckles, beltlocks, spoons, sugar tongs, crosses, watch chains, links, instrument cases, pencil cases and pencils, nail clippers, candle snuffers and snuff boxes, in steel, pinchbeck and gilt. An overdue account in Amsterdam was due to the customer having married off his daughter recently and being short of money as a result of providing her dowry. In France, there were ways of getting round import restrictions on certain goods, by disguising the parcels as permissible goods and placing them in the centre of the shipping casks, surrounded by non-restricted goods, so that customs inspectors who drilled into the casks and checked the first packages they came to would find nothing to confiscate.1

1. ‘A “Commercial” on the Continent a Hundred Years Ago’, in Birmingham Weekly Post, series of letters re-printed from 28 April 1877

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

Birmingham: “The Toyshop of Europe”

Birmingham: “The Toyshop of Europe”

Toys in Birmingham

Toys in Birmingham

John Taylor and Matthew Boulton

John Taylor and Matthew Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: From Snow Hill to Handsworth

The Soho Manufactory: From Snow Hill to Handsworth

The Soho Manufactory: The Ingenious Mr Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: The Ingenious Mr Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: Industrial Tourism

The Soho Manufactory: Industrial Tourism

The Soho Insurance Society: Ahead of its time

The Soho Insurance Society: Ahead of its time

Birmingham Toys: Makers and Materials

Birmingham Toys: Makers and Materials

Birmingham Toys: The Hallmark

Birmingham Toys: The Hallmark

Birmingham Toys: Made at Soho

Birmingham Toys: Made at Soho

Birmingham Toys: “Cut Steel”

Birmingham Toys: “Cut Steel”

Birmingham Toys: Manufacturing Techniques

Birmingham Toys: Manufacturing Techniques

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: The Home Market

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: The Home Market

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Export Markets

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Export Markets

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Travelling Salesmen

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Travelling Salesmen

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Agents

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Agents

Summary and Developments

Summary and Developments