The Escape of the Russells from Birmingham to France

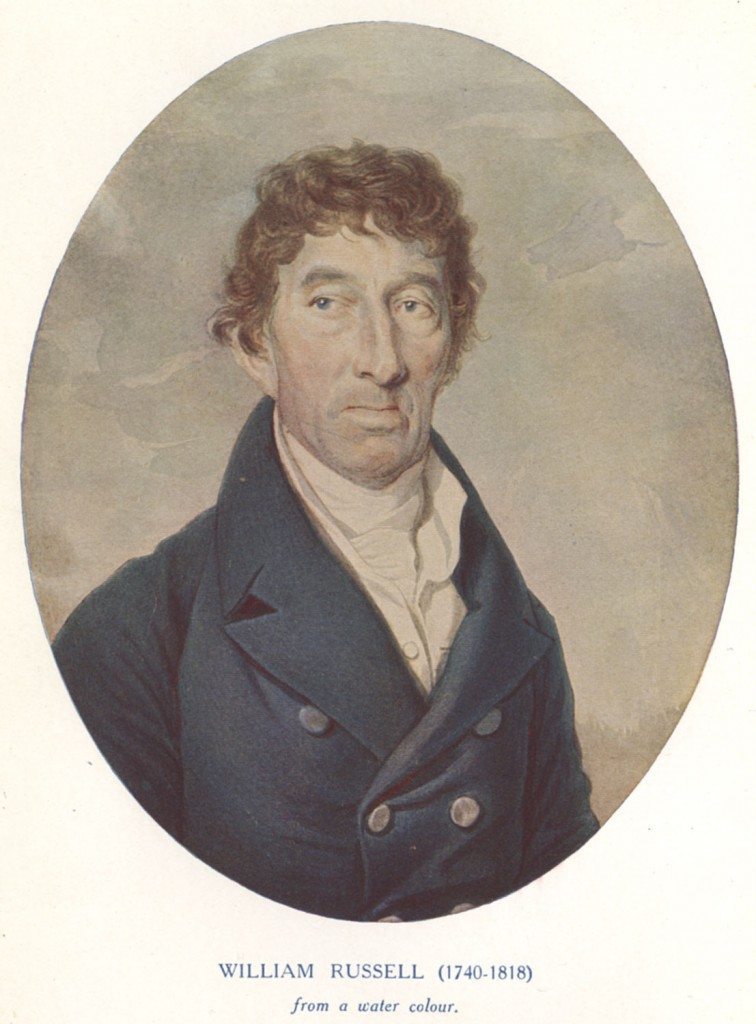

Image: William Russell (1740-1818). Jeyes, S H, The Russells of Birmingham in the French Revolution and America 1791-1814 (London, George Allen & Company, Ltd., 1911).

Image from: Local Studies and History, Birmingham Central Library

The Russell family set sail from Falmouth the following August, but four days into the voyage their ship was intercepted by a French frigate and they were taken prisoner. For the next 40 days while the ship hunted the coastline for other prizes, they slept fully-dressed on the floor among the ship’s stores and vermin, sharing one spoon for their food, the passing days marked by thrice-daily singing of the Marseillaise. Far from fainting with fear, Martha seems to have got a taste for life on board, writing of the exhilaration of chasing after other vessels at 12 knots, and waiting eagerly to see if the boarding party had found any potatoes in the captured ship – potatoes being something they were missing, evidently. They were also impressed with the French sailors’ dancing.

Over the course of five months the Russells were transferred to several different ships, manned by crews whom Martha describes as smelling shockingly of garlic and swarming with “live creatures”. At last, on 26 December 1794 they were set ashore at the French port of Brest and set off for Paris.

Mary Russell’s diary takes up the account to describe life in Paris over the next six months. The family took an apartment overlooking the Tuileries, but though richly furnished it was not a luxurious life. That January (1795) it was so cold that the water froze as they washed their hands, and bread was scarce. In post-Robespierre Paris it was unwise to appear on the streets looking too clean or well-dressed – marking one out as a possible aristocrat. Sitting in on debates in the National Convention, they were unimpressed with the new French regime, Martha describing them as for the most part “dirty, mean, shabby-looking fellows… some in fur caps, others in red and blue caps, some apparently in dirty nightgowns, others shabby great coats, many that had not been shaved for a week at least, and some that had not a comb in their hair that day.”

“Madame Guillotine” had not retired – William Russell and his son went to an execution where, wrote Mary, they saw 16 people guillotined in 13 minutes. The women visited galleries, museums, cathedrals, abbeys, and the Sèvres china factory, Mary describing the architecture at some length. At the Palais Royal, “the beauty and elegance of the shops …. was beyond description at night when they were all lighted up, it was past conception enchanting.” They met Mary Wollstonecraft, another radical, then living in France with her American lover, Gilbert Imlay, as his wife. Mary Wollstonecraft’s Thoughts on the Education of Daughters had been published in 1787, and her best-known work Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792. The Russells several times attended the theatre with “Mrs Imlay” and Mary Russell compared the English and French stage versions of heaven and hell, observing that at the Paris Opera “the French heaven was I must confess much superior in taste and beauty to the English tho’ the English hell was far more terrific and dreadfull than the French”.

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

The other side of the Coin: Women and the Lunar Men

The other side of the Coin: Women and the Lunar Men

The Lunar Men and the Status of Women

The Lunar Men and the Status of Women

Miss Ann Boulton

Miss Ann Boulton

Sabrina and Lucretia: a failed experiment

Sabrina and Lucretia: a failed experiment

Educating Amelia

Educating Amelia

Maria Edgeworth

Maria Edgeworth

Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, the “Queen of the Blues”

Mrs Elizabeth Montagu, the “Queen of the Blues”

Mary Knowles

Mary Knowles

Lady Catherine Wright

Lady Catherine Wright

Mary and Martha Russell and the Birmingham Riots of 1791

Mary and Martha Russell and the Birmingham Riots of 1791

The Escape of the Russells from Birmingham to France

The Escape of the Russells from Birmingham to France

The Russells in America

The Russells in America

The Return of the Russells to England

The Return of the Russells to England