The Soho Insurance Society: Ahead of its time

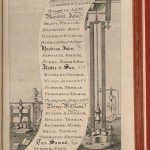

Image: Rules for Conducting the Insurance Society belonging to the Soho Manufactory. The image is an imaginative display of how Boulton wanted to represent his business as a caring concern. The scene connects wisdom, art, prudence and industry and is a remarkable attempt to marry classical imagery with 18th century industry. A more detailed description follows in the text.

Image from: Birmingham City Archives and Soho House Museum

Matthew Boulton claimed to have 1,000 workers at the Soho Manufactory, including men, women and children. Among the innovations at Soho was one of the world’s earliest works insurance schemes. Workers’ ‘friendly societies’ or ‘box clubs’ began forming in manufacturing areas in the mid-18th century. Societies of this kind, which often met in pubs, were early forerunners of the trade union movement. Societies based in the workers’ place of employment were rare. Exactly when the Soho society started is uncertain, but it was definitely before 1782. That year, Dr Thomas Percival of Manchester wrote to ask how it worked. Boulton’s manager John Hodges answered the letter, and his reply makes it clear that the scheme had already been in operation for some time:

Inclosed herewith for your friends inspection is a printed paper of the rules of the Soho Club, which have been adhered to, with very little alteration, ever since its institution, and have been found to answer the chief intent, ie, that of being a sufficient support for any of its Sick Members during the time of illness. From the contributions of People who visit here, with the weekly payments of the Workmen, it has scarcely ever been exhausted, tho’ several times it has been very low, and it of course rises or falls according to the number of the sick. At this time it is what is deem’d very rich, having near £120 in Stock. 1

The Rules which Hodges sent Dr. Percival still exist. They are printed on a sheet headed by an engraving showing the Manufactory in the background. In the foreground sits a worker with his arm in a sling, surrounded by figures representing Art, Prudence, and Industry. Other components of the design represent fidelity, stability, plenty, commerce, and wisdom. Near the Manufactory are ‘little Boys busy in designing, &c, which shew that an early Application to the Study of Arts is an effectual Means to improve them’.2

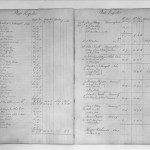

From the rules, we can get a good idea of how the scheme was run. Every male worker earning two shillings and sixpence per week or more was a member of the society. New employees received a copy of the rules, payment for which served as a joining fee. Men paid one shilling to join, boys aged 14-18 eightpence, and younger members sixpence. For new employees aged 45 or over membership was optional. Women were evidently not included in membership. Whether, as low-paid workers, they would have been considered for discretionary grants (see below) is not specified.

Having joined, each member paid regularly into the ‘treasure box’ on a sliding scale according to his earnings. Weekly contributions ranged from a halfpenny from those earning two shillings and sixpence per week, up to fourpence from those earning twenty shillings (£1) a week. Workers whose wages were below two shillings and sixpence a week did not pay into the scheme, but could be made a discretionary grant from it in times of hardship due to sickness. Payments were collected every Monday morning. Careful records of members, payments and benefits were to be kept.

Members of the Society who were off sick could start drawing benefit after they had paid in to the scheme for three months. Those injured in accidents at work could draw from it immediately. A sliding scale of benefits operated, ranging from one shilling a week for the lowest paid members (contributing a halfpenny a week), to eight shillings a week for the highest paid (contributing fourpence a week). These payments would continue in case of need as long as the fund contained at least £100.

The scheme was managed by a committee of six workers, whose conduct was subject to inspection by six ‘elders’ appointed by Mr Boulton. Workers claiming sickness benefit were to be visited daily by a committee member.

There was a range of fines and forfeits to discourage both fraud by workers, and inefficiency or fraud by the committee. Committee members were fined for failing to attend meetings, and workers were fined for fraudulent claims (including working elsewhere while claiming to be off sick), and begging for tips from “gentry” visiting the Manufactory. Senior staff who guided these visitors round were fined for keeping money given to them by the visitors instead of putting it in the “treasure box”. One rule stated: “As it is for the health, interest, and credit of the men as well as masters, to keep this MANUFACTORY clean and decent, it shall be deemed a forfeit of one shilling to the box for any one found guilty of any indecencies, or keeping dirty shops…”.

In cases of severe hardship, the committee had discretion to increase benefit. However, if the sickness was found to be due to drunkenness, debauchery, quarrelling or fighting, the worker would not be entitled to receive any sick pay for ten days. In cases of death in service, the deceased’s family would receive help towards funeral expenses, at the rate of thirty shillings for the lowest-paid contributor to a hundred shillings (£5) for the highest-paid.

1. MBP 147, Letterbook ‘N’, p. 48, John Hodges (Soho) to Dr. Thomas Percival (Manchester), 16 November 1782

2. Rules for Conducting the Insurance Society Belonging to the Soho Manufactory (framed copy at Soho House)

« Previous in this sectionNext in this section »Continue browsing this section

Birmingham: “The Toyshop of Europe”

Birmingham: “The Toyshop of Europe”

Toys in Birmingham

Toys in Birmingham

John Taylor and Matthew Boulton

John Taylor and Matthew Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: From Snow Hill to Handsworth

The Soho Manufactory: From Snow Hill to Handsworth

The Soho Manufactory: The Ingenious Mr Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: The Ingenious Mr Boulton

The Soho Manufactory: Industrial Tourism

The Soho Manufactory: Industrial Tourism

The Soho Insurance Society: Ahead of its time

The Soho Insurance Society: Ahead of its time

Birmingham Toys: Makers and Materials

Birmingham Toys: Makers and Materials

Birmingham Toys: The Hallmark

Birmingham Toys: The Hallmark

Birmingham Toys: Made at Soho

Birmingham Toys: Made at Soho

Birmingham Toys: “Cut Steel”

Birmingham Toys: “Cut Steel”

Birmingham Toys: Manufacturing Techniques

Birmingham Toys: Manufacturing Techniques

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: The Home Market

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: The Home Market

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Export Markets

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Export Markets

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Travelling Salesmen

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Travelling Salesmen

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Agents

Salesmen, Customers and Competitors: Agents

Summary and Developments

Summary and Developments