Thomas Lombe (1685 – 1739)

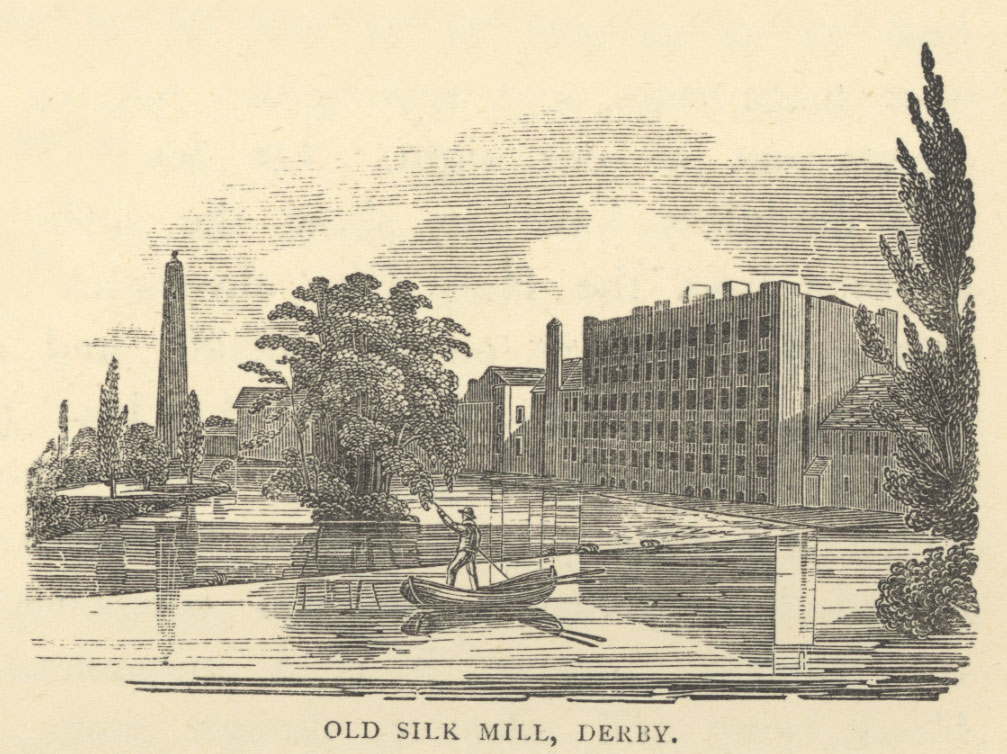

Image: Old Silk Mill, Derby. John Keys, Sketches of Old Derby and Neighbourhoods(London and Derby, 1895)

Two brothers were responsible for the development of successful factory-based silk production in Britain. They were John Lombe (1693 – 1722) and Thomas Lombe (1685 – 1739). The Lombe family had originally come from Norfolk where they were wool merchants and engaged in weaving silk and wool in the reign of Elizabeth I. Thomas inherited the family business and John, who began work as an apprentice boy, showed an aptitude for developing machinery and made suggestions for ways of improving spinning silk thread. He began to work for a retired Derby solicitor, Thomas Cotchett who had established a silk mill in Derby on a small marshy island in the River Derwent close to the centre of the town. The factory was built in 1702 by the notable Derby engineer, George Sorocold (b. 1668) and used Dutch machinery for spinning silk. However, it was not able to produce good quality silk thread.

The best European silk was spun in the Kingdom of Sardinia in Northern Italy. John Lombe determined to find out the secret of Italian success. This was dangerous as governments and businesses protected industrial processes from spies. The Sardinian government imposed the death penalty for those who stole technological ideas. In 1714, financed by his brother, John Lombe sailed for Italy as a tourist and visited silk mills. However, he was not able to learn how the machinery worked until he bribed his way into securing employment as a machine winder in one of the mills. At the end of the day, he stayed on and sketched the machines and smuggled the drawings in bales of silk which were sent to England via Thomas Lombe’s agents in Livorno. John Lombe’s espionage was discovered, but he managed to escape. In England, a £30,000 factory was built next to Cotchett’s original mill also designed by George Sorocold. New machines were patented and installed in 1718 which transmitted the energy from water wheels over five floors by a system of cogs and gears. Scorocold’s design was a major achievement. The success of the Derby Mill encouraged the development of a silk industry in Chesterfield, London, Macclesfield, Manchester, Norwich and Stockport.

John Lombe died in 1722 at the age of 29. He was possibly poisoned by an Italian woman who had known John Lombe in Italy and secured employment in the Derby Mill. After John’s death, the silk mill continued to flourish. Initially John’s share in the business passed to a cousin, but after his death, Thomas Lombe ran the business. He was honoured with a knighthood by King George I.

Though there a few surviving records of the original mill, we know a little about working conditions from The Life of William Hutton, written by the first historian of Birmingham. William Hutton (1723-1815) worked at the mill as a boy in the 1730s between the ages of seven and fourteen. He hated the work and described rising at five each morning, submitting himself to the cane from his master and having as his companions “the most rude and vulgar of the human race, never taught by nature, nor ever wishing to be taught.”

In 1910 the building was badly damaged by fire and it was rebuilt as a more modest structure. The bell tower and the foundations survive from the original eighteenth-century building. The Silk Mill is no longer a factory, but it serves, very appropriately as Derby’s Industrial Museum.

Sources and Further ReadingBerg, Maxine, The Age of Manufactures 1700 – 1820 (Routledge, 1994)

Bush, Sarah, The Silk Industry (Shire Publications)

Defoe, Daniel, A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1720)

Hutton, William, History of Derby (1791)

Hutton, William, The Life of William Hutton (Brewin Books, 1998)

Rees’s Manufacturing Industry 1819-20

Warner, F, The Silk Industry of the UK (1921)